Who Were the Moabites? Origins, Israel’s Enemies, and Ruth

This post is part of the series “King Jehoshaphat's Prayer”

-

King Jehoshaphat’s Prayer: 8 Bible-Backed Steps to Trade Panic for Peace

-

Who Was Jehoshaphat Anyway?

-

Who Were the Moabites? Origins, Israel’s Enemies, and Ruth 👈 you are here

-

Sitting In the Shadows of History: The Story of the Ammonites

-

Everywhere and Nowhere: The Story of the Amalekites

The Moabites—descendants of Lot’s son Moab—settled east of the Dead Sea. Worshipers of Chemosh, they were ruled by kings such as Balak and Mesha, clashed with Israel for centuries, yet through Ruth became ancestors of King David and, ultimately, Jesus.

This is the story of the Moabites.

The Scandalous Birth of Moab

To find the beginning of the Moabites, we have to go back pretty far, to a more-or-less unknown guy named Terah. Terah lived in a city called Ur, and he had three sons, one of whom you’ve probably heard of: Haran, Nahor, and Abram. Haran had a son named Lot. Then Haran died. Then Terah died.

Abram adopted Lot, and the two of them moved around together. Eventually, Lot settled in a town called Sodom. You may know that Sodom wasn’t populated with model citizens, and God decided to destroy it. But before He did, He sent angels in to get Lot and his family out before the fire fell (Genesis 19:12–13).

There’s a horrible scene with the men of the city, the angels, and Lot’s daughters (Genesis 19:4–11), but ultimately Lot and his family escape. Lot’s wife disobeys the instruction not to turn back and is turned to salt (Genesis 19:26). Lot and his daughters reach safety exhausted, far away from home, and alone.

They had originally planned to live in a little village called Zoar, but Lot fears the locals, so they go up to a cave in the hills. While they’re up in the hills, Lot’s daughters suddenly realize that every man in their lives is dead, killed by the wrath of God. Panicking and not thinking clearly, they get Lot drunk and sleep with him on subsequent nights (Genesis 19:31–35).

Lot’s younger daughter, who never gets a name, gives birth to a boy and names him Ben-Ammi, “son of my kin”—that is, “product of incest”. Not the nicest of names.

Lot’s older daughter, who also never gets a name, also gives birth to a boy, and she names him Moab, which sounds an awful lot like the Hebrew for “from father”. Again, inauspicious. And we read in Genesis 19:37,

The firstborn [daughter] bore a son and called his name Moab. He is the father of the Moabites to this day.

Moab vs. Israel: A Long History of Conflict

Moab and Israel never get along. And they keep running into each other.

Because Abram had adopted Lot, God blessed Lot’s descendants along with Abram’s, and He gave Moab the land of Ar, just east across the Jordan River from Jericho. According to Deuteronomy 2:11, they had to drive out a race of giants called the Emim.

The next time we see them, though, is during the Exodus from Egypt, when God tells Moses to go around that land instead of through it, because the land is His gift to Moab (Deuteronomy 2:9).

Fast forward, and it’s Numbers 21:26–30. The Moabites are getting run out of their land by King Sihon and the Amorites. When the Israelites get there, they beat the Amorites back—not for the Moabites’ sake, but because Sihon had refused Israel passage under Moses.

After their victory, they camp on the border of Moab. Unfortunately, living together doesn’t work out so well for Israel.

King Balak of Moab sees all these Israelites camping on his border, and he gets nervous. But Israel has just defeated the Amorites, who had previously defeated the Moabites, so he cleverly decides against going to war. He comes up with a better idea: he’ll get a prophet, Balaam, to curse the Israelites, and maybe they’ll go away.

Here, in Numbers 22–24, we get an amazing story of Balak and Balaam and a talking donkey and an angel with a sword. And rather than curse the Israelites, Balaam blesses them… four times! Not what Balak intended.

Later as a consequence of Balak’s attempted curse, God forbids the Moabites from joining the assembly of Israel (Deuteronomy 23:3–6).

Anyway, the Israelites spend enough time there to start intermarrying with Moab, and even start worshipping the local god, Baal-peor. In Numbers 25, we read that God responds with a swift plague and a command to Moses to kill the chiefs of the idolatrous clans. The plague was only stopped when Phinehas the priest, the grandson of Aaron, ran a spear through an Israelite man and the foreign woman he had brought into the camp explicitly against God’s orders.

By that point, 24,000 Israelites had already died.

The Assassination of Eglon

You’d think after incest, a talking donkey, and a plague, the story of Moab couldn’t get crazier.

You’d be wrong.

At some point during the period of the judges, King Eglon of Moab, allied with the Ammonites and Amalekites, conquers Israel. (The time of the judges is chaotic for Israel, a seemingly endless cycle of sin and war and salvation and peace.) Eglon rules Israel for eighteen years.

But eventually Israel turns back to God, and He hears their cries. Enter Ehud, “a left-handed man” (Judges 3:15). Ehud is appointed to bring Eglon the tribute Israel owed Moab, and he has a plan.

After delivering the tribute, Ehud tells Eglon he has a secret message for him from God, but he can only tell him when they are alone. So Eglon sends his guards away, Ehud pulls out the short sword he has concealed on his right thigh, and stabs Eglon in the stomach.

It’s at this point we learn two things. First, apparently there were no left-handed warriors in those days, because the the guards surely checked his left thigh for weapons, and somehow didn’t think about the other way around.

Second, Eglon was a very fat man (Judges 3:17). So fat that his stomach closes back around the eighteen-inch sword, and Ehud simply walks out with Eglon seemingly intact.

Hours later, Eglon’s servants were standing around, intensely embarrassed because Ehud had left him in the “well-ventilated room”—probably the bathroom—and they didn’t want to interrupt him, but also it had been a while, and you don’t yell to a king, “What happened, you fall in?!”

Eventually, the servants open the door and Eglon grossly rolls out, dead. But by this time Ehud has made it home, gathered an army, and re-crossed the Jordan river.

Ehud’s army kills 10,000 Moabites in the sneak attack. Moab gives up control of Israel, and Ehud becames judge of Israel. And for eighty years, the land has peace.

Moab in the Days of the First Kings of Israel

But the Moabites don’t go away. They just disappear for a while.

Fast-forward to Saul’s reign as king, and we see him at war with Moab (1 Samuel 14:46–48). Of course, Saul was at war with a lot of Israel’s neighbors. But Moab is unique, because while David was running from Saul, he leaves his parents with the king of Moab for protection. At the advice of the prophet Gad, David himself keeps moving (1 Samuel 22:3–4).

Later (2 Samuel 8:2), despite their previous care for his parents, David finally defeats the Moabites. He gruesomely measures the defeated army with a rope, and slaughters two thirds of them by area.

Another generation later, and Solomon is getting friendly with Moab again. He has apparently forgotten all of Israelite history up to this point, and he marries Moabite wives (1 Kings 11:1), the thing that had earlier caused a plague that killed 24,000 Israelites. He even builds an altar to Moab’s primary god Chemosh (1 Kings 11:7). Not a good move for a king chosen by Yahweh. (These events are part of Solomon’s descent into idolatry, which eventually results in his weak son Rehoboam fracturing the kingdom into north and south and never reuniting.)

The Moabite Stone: Moab’s Side of the Story

The next story of Moab and Israel comes not from the Bible but from an archaeological artifact called the Mesha Stele, or the Moabite Stone (Mesha was a king of Moab, as we’ll see).

The Moabite Stone was written in about 840 BC and re-discovered in 1868. It’s written in an ancient Hebrew script, and it tells the story of how Chemosh, the god of Moab, had become angry and allowed Israel to defeat them (sound familiar?), but later relented and led them to victory. We don’t have a definitive parallel in the Bible, but this is probably the story of how King Jeroboam of Israel defeated Moab and how they rebelled under King Omri. Omri, who is mentioned by name on the stone, was the evil King Ahab’s father.

The story of the stone then skips forward several generations and tells of King Mesha of Moab, who survived assaults from both King Jehoshaphat of Judah and King Joram of Israel (read the rest of that story here) and freed Moab. This story is almost certainly the story of 2 Kings 3, but from the Moabite perspective.

More Wars, More Kings, Same Old Moab

During the period of the kings of Israel and Judah, the nations continue to clash repeatedly.

After King Omri of Israel puts down one Moabite rebellion, Moab rebels again under the weak and short-lived king Ahaziah, Omri’s grandson (2 Kings 1:1).

Moab rebels again against Ahaziah’s younger brother Joram, who succeeded him on the throne of Israel. Joram, not as weak as his brother, asks King Jehoshaphat of Judah for help, and the two of them go to war. On the way to battle, however, they run out of water (in the desert, water is a necessary ingredient for victory). The kings visit the prophet Elisha—yes, that Elisha—for help, and he totally blows off Joram, because Joram is just like his father Ahab: anti-God and proud of it.

But for Jehoshaphat’s sake, Elisha tells them how to trick the Moabites by digging holes in the desert. God fills the holes with water, and the Moabites mistake it for blood. They assume Jehoshaphat and Joram have killed each other, and they charge, only to be met by two full-strength armies. King Mesha of Moab, hanging back, sacrifices his first-born son to Chemosh, but it does him no good and his army is defeated. Israel and Judah destroy the land, pulling up trees and stopping up springs, even scattering rocks anywhere that could grow food.

The wars continue. While Jehoshaphat was still king of Judah, Moab allies yet again with the Ammonites to attack Judah. Jehoshaphat turns to Yahweh for help, and [it doesn’t go well for Moab][kjp-post] (2 Chronicles 20).

Moab continues to be a thorn in Israel’s side, raiding the nation (2 Kings 13:20) until Jeroboam II of Israel subdues them again (2 Kings 14:25), but then God sends Moab against Israel yet again to punish them for their own rebellion against Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon (2 Kings 24:1–2).

Moab and the Prophets: Isaiah and Jeremiah

Moab is a constant presence in the life of Israel, living just across the Jordan river, so it’s not a surprise the prophets take notice as well.

The first time we see Moab in prophecy is in the lament of Isaiah 15. Isaiah describes an invasion of Moab from Ar on the border to the central city of Kir (Isaiah 15:1). It’s hard to date the prophecy, so it could refer to Assyria’s final conquest of the area under Sennacherib (705–701 BC) or it could refer to an as-yet-unknown event.

Anyway, Zion offers Moab hope, as it does to anyone desiring to live in the presence of God and follow His laws, but Moab’s pride prevents it from accepting help, and as a result, the lament continues into Isaiah 16.

Speaking of invasions from massive eastern empires, Jeremiah mentions Moab as one of the many nations conquered by Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon (Jeremiah 27:1–8).

The Fall of Moab: Back to Sodom

Finally, Moab ends exactly as it began: in a firestorm of sin.

Zephaniah 2:8–9 tells us that God will make Moab as Sodom, and Ammon as Gomorrah. Thinking back a thousand years or so, the destruction of Sodom that drove Lot into the hills and his daughters into his bed is where Moab (and Ammon!) began. Centuries of strife kicked off by that desperate first sin end the same way.

And indeed, some time around 400 BC, the Nabatheans come through Moab and wipe it off the map, never to be heard from again.

From Curse to Blessing: Moab’s Redemption

It is one of the glories of the Bible that we can so often say with Joseph,

you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today.

So far, we have seen the strife brought about by the sin of Lot’s daughters and the wars of Israel and Moab. We have seen idol worship progress to the point of child sacrifice. And yet, “God meant it for good.”

Because Moab is so important in the history of Israel, we learn a lot of Moabites’ names: Balak, Eglon, Mesha… and Ruth.

Ruth, of course, was a Moabitess. Her story is famous, so I will not retell it here except for three notes.

First, in a kind of mixed-up parallel to Lot’s daughters, we never learn which of Naomi’s sons Ruth marries. Lot had two daughters, and we learn which was the older and which was the younger but never their names. Naomi has two sons, Mahlon and Kilion, but we never learn which was older or younger or which married Ruth or Orpah.

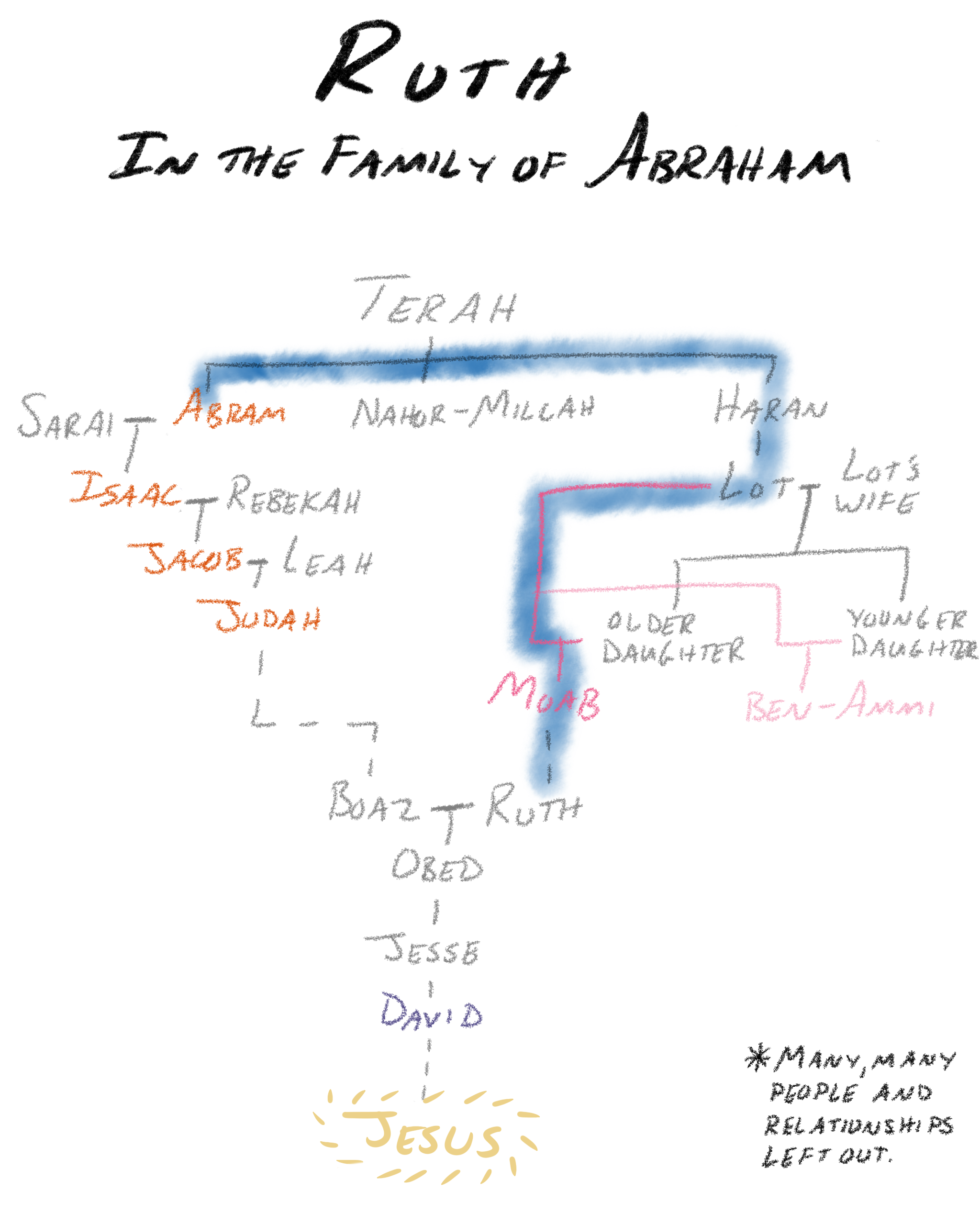

Second, now that we know that Moab was Lot’s son (and grandson), we can actually see that Ruth is related to Abraham through Terah. So when she marries Boaz, whose lineage in Israel is well-documented, they unite two branches of a family that was sundered centuries before.

And third, Ruth’s son was Obed, and Obed’s son was Jesse, and Jesse’s son was David, and David’s son was Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ. Just as Jehoshaphat shows back up in Matthew 1:8, his serial enemy Moab shows back up in Matthew 1:5 in the person of Ruth.

These two warring nations, one destroyed and the other oppressed, are united in Christ almost a thousand years later.

Now that’s a story.

This post is part of the series “King Jehoshaphat's Prayer”

-

King Jehoshaphat’s Prayer: 8 Bible-Backed Steps to Trade Panic for Peace

-

Who Was Jehoshaphat Anyway?

-

Who Were the Moabites? Origins, Israel’s Enemies, and Ruth 👈 you are here

-

Sitting In the Shadows of History: The Story of the Ammonites

-

Everywhere and Nowhere: The Story of the Amalekites