Sitting In the Shadows of History: The Story of the Ammonites

This post is part of the series “King Jehoshaphat's Prayer”

-

King Jehoshaphat’s Prayer: A Scriptural Response to Fear

-

Who Was Jehoshaphat Anyway?

-

From Sodom and Gomorrah to Jesus: The Story of the Moabites

-

Sitting In the Shadows of History: The Story of the Ammonites 👈 you are here

-

Everywhere and Nowhere: The Story of the Amalekites

The story of Ammon begins like the story of Moab.

That article tells the whole story, but here’s the short version: after escaping Sodom and taking refuge in the hills, Lot’s daughters panic about the lack of men in their lives. Their mother had turned into a pillar of salt because she looked back at the city as it burned (Genesis 19:26), so they had no one to advise them. Taking matters into their own hands, they decide to get their father drunk and sleep with him to guarantee them children. And we read in Genesis 19:38,

The younger [daughter] also bore a son and called his name Ben-ammi. He is the father of the Ammonites to this day.

“Ben-ammi” means “son of my kin”—or, more crudely, “product of incest.” In a world where names are meaningful, Ben-ammi starts off on the wrong foot.

Ammon and Moab

Ben-ammi is the father of the Ammonites, and his half-brother Moab is the father of the Moabites. We see Ammon and Moab together a lot. In fact, in almost half of the chapters where Ammon is mentioned, Moab is also mentioned1.

The similarities are striking. Like Moab, Ben-ammi is the son of Lot. When Abram adopted Lot, Lot inherited God’s promises. As a result, when Israel invades Canaan during the Exodus, God instructs them to leave Ammon alone because He had given them that land (Deuteronomy 2:10). Just like Moab (Deuteronomy 2:9). And also like Moab, that land that God gave the Ammonites was full of giants, the Rephaim2, which Ammon had to kick out (Deuteronomy 2:20–22).

Moab and Ammon are so intertwined in the histories of Israel that sometimes they seem grouped more by habit than by history. For example, when Moses declares that “No Ammonite or Moabite may enter the assembly of the Lord”, he gives two reasons: they did not support Israel on its flight from Egypt, and they hired the prophet Balaam to curse Israel (Deuteronomy 23:3–4). But in the entire story of King Balak and Balaam and the talking donkey, Ammon is never mentioned.

But that doesn’t mean they leave Israel alone, either.

After Israel conquers Canaan, it’s not long before Ammon becomes a problem. At first, it’s because, just before Israel got there, Ammon had conquered some Amorite territory (Judges 10:13). When Israel showed up, they defeated King Sihon of the Amorites and drove the Amorites back to the Jabbok River, which was the border with Ammon (Numbers 21:21–24). Ammon did not appreciate losing what it had just conquered, so when King Eglon of Moab decided to fight off these newcomers, Ammon happily joins him, and Israel serves Eglon for eighteen years.

There Is Ammon in Gilead

As part of Eglon’s victory, Ammon occupies land belonging to Israel, just across the river Jordan in Gilead. After eighteen years of this, Gilead is ready for a break, but when they call for a military leader, nobody stands up.

Desperate, they send for Jephthah, the outcast son of a prostitute whom they had chased off years earlier. Jephthah agrees to fight for them if they’ll put him in charge after he wins. They agree, and he gets ready to fight.

Now comes one of the most tragic stories in Scripture. To understand what’s about to happen, you have to know how houses in the ancient near east were designed. Bear with me; it’s important, I promise. These houses were the original great room: a stable at the front, just inside the door; a step up to the kitchen-living room-bedroom; and a guest room at the back, away from the animals3.

Now Jephthah knows he needs supernatural intervention to beat the Ammonites, so he promises God that he will sacrifice the first thing that comes out of his house if he returns victorious—surely it will be a cow or a goat or something.

God gives Gilead the victory, and Jephthah not only conquers their army but also defeats twenty Ammonite cities. Upon his return, though, instead of an animal wandering out of his house, his daughter runs out, dancing and playing a tambourine to celebrate his victory. Surprisingly sanguine, she asks only for two months to wander the mountains and mourn; he agrees, and when she returns, he sacrifices her as a burnt offering, just as he vowed (Judges 10:6–11:40).

As a post-script, the Ephraimites get angry with Jephthah for going to war without them; they wanted some of the glory. So, naturally, they go to war against him. He beats them soundly and captures the fords across the Jordan to keep the Ephraimites on the other side. But they’re all Israelites—how to tell the difference? They come up with a test: they make every man crossing the river say, “shibboleth.” But the Ephraimite accent pronounced the word, “sibboleth,” so they are easily discovered (Judges 12:1–6).

Ammon and the Kings

Like Moab, Ammon shows up in some of the biggest stories of the Old Testament.

Ammon and Saul

In the time of Saul, Ammon once again goes to war against Israel (1 Samuel 11). And once again, they start in Gilead, just across the river. But Jephthah’s been dead for a while, and they still don’t really have a leader. So they ask Ammon for seven days to get help, and they agree to surrender if they can’t find any.

When Saul hears the news, he’s plowing with a team of oxen. The Spirit of God fills him, and he slices up the oxen and sends them throughout Israel as a suggestion of what he will do to them if they do not come join the defense.

It works: 300,000 Israelites come to fight, along with 30,000 from Judah, and they destroy the Ammonites. This victory cements Saul’s coronation as king of Israel: Samuel had anointed him at Ramah (1 Samuel 10:1) and proclaimed him king at Mizpeh (1 Samuel 10:17–27), and now he assumes the throne on the heels of this victory, which he ascribes directly to God. Samuel shrewdly recognizes this opportunity to renew Israel’s dedication to God and present Saul as the new king at the same time. He reminds them that they asked for a king specifically to protect them from the Ammonites—and here he is!

Saul fights the Ammonites throughout his reign (1 Samuel 14:47); it takes David to finally subdue them after he becomes king (2 Samuel 8:11–12).

But they don’t stay subdued.

Ammon and David

Nahash, the Ammonite king during the wars with both Saul and David, dies, and his son Hanun decides he’s had enough of peace with Israel. David sends messengers to console Hanun on his loss, and Hanun sends them back with half their beards shaved off and half their robes cut loose—presumably the bottom half, for maximum humiliation (2 Samuel 10:1–5).

David, not pleased, sends his general Joab to avenge the men. Hanun, realizing he’s made a terrible mistake, hires 33,000 Syrian mercenaries to help defend the Ammonite capital Rabbah4.

It doesn’t work.

Joab trusts in God, the Syrians turn and flee, and Joab takes the city. At some point, the Syrians become embarrassed that they fled so easily. They gather a larger force and turn back to fight, but David slaughters them, killing 700 charioteers and 40,000 horsemen, including their commanding general (2 Samuel 10:15–19).

You might remember that city name, Rabbah, from a much more famous story. In the next chapter (2 Samuel 11), Joab has gone out to lay siege to Rabbah and fight those Syrians. But David stays behind in Jerusalem, and gets himself into trouble with a woman named Bathsheba. It is those Ammonites, the ones that hired the Syrians, that kill Uriah, Bathsheba’s husband. So the Ammonites are now intimately connected to David’s most famous sin and, consequently, the birth of his son Solomon.

Ammon and Solomon

Now Solomon doesn’t fight many battles, because David defeated all of Israel’s enemies. But he nonetheless struggles with the Ammonites.

As part of his expansion of the kingdom of Israel, Solomon enters a huge number of marriage alliances; by the end of his life, he has seven hundred wives. Those wives introduce him to their gods: Ashtoreth of the Sidonians, Chemosh of the Moabites, and Milcom of the Ammonites. Milcom, also known as Molech, apparently desires child sacrifice (2 Kings 23:10), making Solomon’s choice to build a sacred place for him even more horrifying (1 Kings 11:1–8).

Because of Solomon’s infidelity, God promises to strip the kingdom away from him and give it to his servant instead of his son. But for the sake of David, he allows Judah to pass to his son.

But out of those seven hundred wives, which is the mother of his heir? Of course, it’s an Ammonite woman named Naamah. Remember that for later.

Ammon and the Others

Ammonite, like its brother Moab, remains a thorn in Israel’s side for hundreds of years:

- Ammon and Moab unite to attack King Jehoshaphat of Judah (2 Chronicles 20). It doesn’t go well for them.

- King Joash of Judah falls to Syria and is wounded in the battle; as he lies wounded, his servants kill him for having murdered the priest Zechariah. Which servants? Zabad the Ammonite and Jehozabad the Moabite (2 Chronicles 24:23–27).

- King Uzziah of Judah collects tribute from the Ammonites (2 Chronicles 26:8), but after he dies, they rebel against his son Jotham, who has to defeat them all over again (2 Chronicles 27:5).

- Much later, about 601 BC, King Jehoiakim of Judah rebels against Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, and God sends an alliance of Chaldeans, Syrians, Moabites, and Ammonites against Judah to destroy it (2 Kings 24:1–3).

- After Israel returns from Babylon and begins to rebuild Jerusalem, Tobiah the Ammonite, probably a regional governor, conspires to re-destroy the city. Nehemiah responds by setting watches and arming the builders, and the city stays intact, as does the now-centuries-old acrimony between the nations (Nehemiah 2:9–10).

- Nehemiah later learns from the book of the law that the Ammonites are not permitted in the assembly of God. He and Ezra both lament that the Jews had been intermarrying with the Ammonites and Moabites, to the point that some children of mixed households couldn’t even speak Hebrew (Nehemiah 13:1–3,23–24; Ezra 9:1–3). They immediately cast the foreigners out of the assembly, not quite yet understanding what it means to be the people of God.

But Ammon and Israel are not always enemies.

When David is on the run from his son Absalom (2 Samuel 7:27–29), Nahash the Ammonite supplies David and his army. This feat is apparently an incredible act of kindness and generosity, because we learn the next day that 20,000 men die in the battle between David and Absalom.

David is no stranger to befriending enemies. You may remember that he entrusted his parents to the king of Moab for protection while he ran from Saul (1 Samuel 22:3–4). And sure enough, one of David’s “mighty men”, those thirty renowned warriors and close friends, was Zelek the Ammonite (2 Samuel 23:37).

At one point, Israel even joins an alliance with Ammon, although the story’s not explicit in the Bible.

The Kurkh Monolith

We learn of this alliance from an artifact called the Kurkh Monolith, which, like the Mesha Stele that tells the story of the Moabite king Mesha, is an ancient secular record.

The Kurkh Monolith was written in the mid-eighth century BC and discovered in 1861, just seven years before the Mesha Stele. Where the Mesha Stele is a story, the Monolith is more of a record of the Battle of Qarqar.

Shalmaneser III of Assyria was on the march, coming south. He had won some epic victories in Mesopotamia and was on his way to Egypt. But between him and Egypt was the entire land of Canaan, which was full of people who were tired of being stomped on by massive empires.

Eleven nations allied together, led by Ben Hadad of Syria and King Ahab of Israel, to resist Shalmaneser. The monolith records that Ahab sent 2,000 chariots and 10,000 soldiers; Ben Hadad sent 1,200 chariots, 1,200 horsemen, and 20,000 soldiers.

King Ba’asa of Ammon sent… 100 soldiers. But he was still part of the alliance, making this one of the only times Ammon and Israel fought on the same side.

Ammon and the Prophets

The prophets of Yahweh hate Ammon. Worshiping a god that demands child sacrifice will have that effect, as will the incredible cruelty they displayed.

Isaiah says that in the restoration of Jerusalem after the downfall of Babylon, Judah and Israel will reunite and enslave Edom, Moab, and Ammon. David likewise, upon conquering Rabbah, set them all to manual labor (2 Samuel 12:26).

Jeremiah repeatedly prophesies the downfall of Ammon (Jeremiah 9:25–26; 25:15–26; 27:1–7). He also tells the story of King Baalis of Ammon sending Ishmael the assassin to kill Gedaliah, the governor of Judah under Babylonian rule. Ishmael abducts some captives, but Jewish soldiers manage to rescue them (Jeremiah 40:13–41:18; 2 Kings 25:22–26).

Jeremiah finally pronounces judgment on Ammon, prophesying that Rabbah “shall become a desolate mound, and its villages shall be burned with fire” because they settled in the land given to Gad (Jeremiah 49:1–6). This settlement probably happened after Assyria invaded Ammon in 734–732 BC. (Just prior to these verses, Jeremiah pronounces a nearly identical prophecy over Moab; they are brothers forever.)

Ezekiel prophesies two defeats of Ammon: one by Babylon (Ezekiel 21:18–24) and one by “the people of the east”, who may also be Babylon (Ezekiel 25:1–7).

Amos pronounces judgment on Ammon for a different reason: “because they have ripped open pregnant women in Gilead” (Amos 1:135). Not content with simply conquering the people prior to Jephthah’s or Saul’s rescue, they slaughtered and dismembered pregnant women. Therefore, God will burn Rabbah to the ground.

Finally, Zephaniah prophesies against Ammon for “taunting [His] people”. In response, God will make Moab and Ammon like Sodom and Gomorrah, so their end will match their beginning, and they will become “a land possessed by nettles and salt pits, and a waste forever” (Zephaniah 2:8–9).

Nubuchadnezzar fulfills many of these prophecies in 582 BC when he destroys Ammon and Rabbah as part of his invasion of the entire world.

The Ammonites mostly disappear after that, popping up once more in Justin Martyr’s Dialogue with Trypho in the 100s AD, which claims that they were “still a numerous people” at that time. But they hadn’t really been heard from in seven hundred years, and they were never heard from again6.

Ammon and Jesus

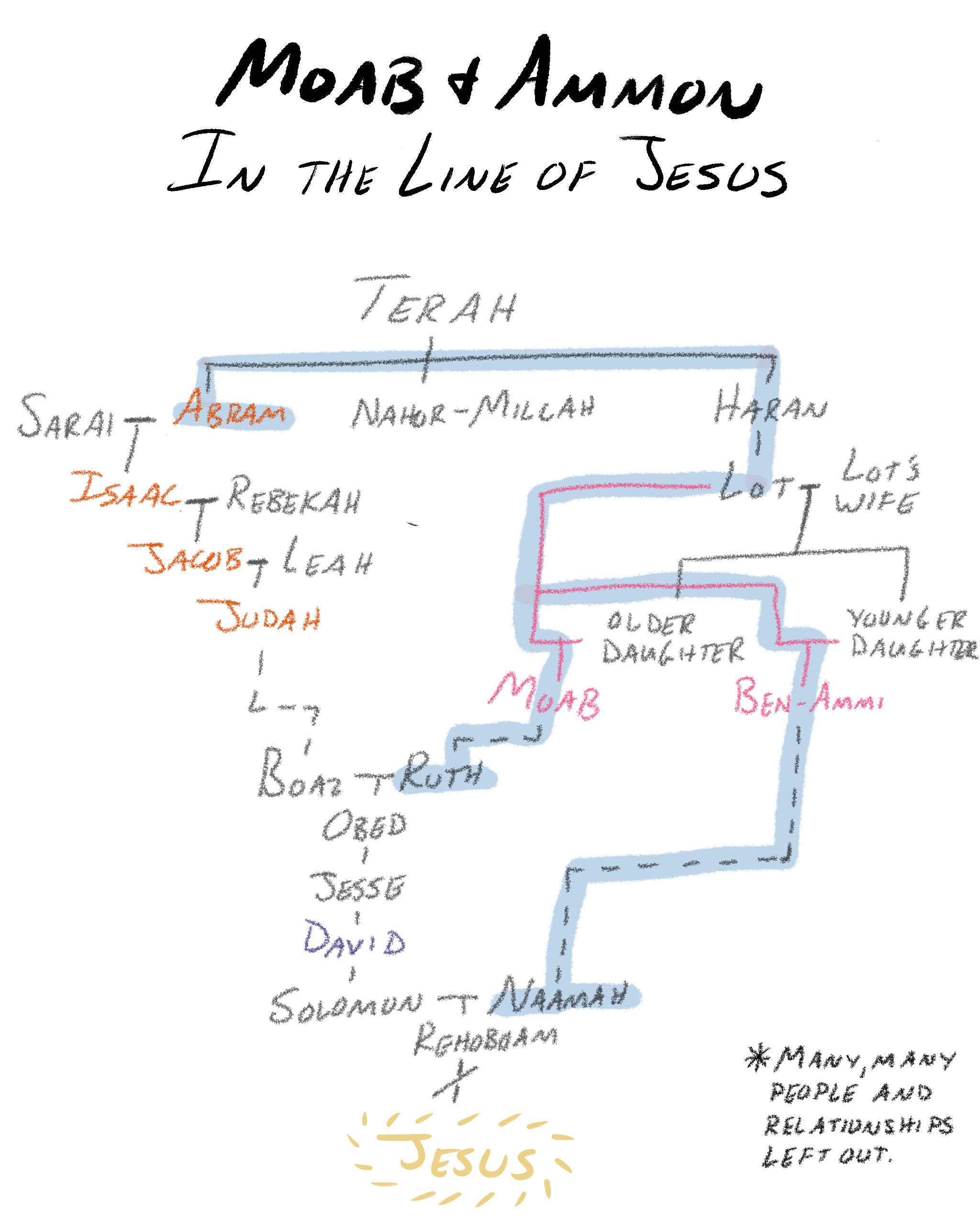

We have already seen that the story of Moab includes Ruth, who eventually marries Boaz and becomes the great-grandmother of King David. She therefore gets a mention in Matthew 1:5 in the genealogy of Jesus.

But there’s a name missing in Matthew 1.

Remember that Rehoboam’s mother was Solomon’s wife Naamah the Ammonite. And Rehoboam is right there in Matthew 1:7. So just four generations after Moab joins the bloodline of Jesus, Ammon does, too.

Why is this fact important? Because it reinforces the idea that Jesus’s bloodline contains people who are not “God’s people”—and in fact are the historic enemies of God’s people. To paraphrase Galatians 3:28, in Jesus, there is no Jew nor Ammonite7.

He came for the whole world, and no one people has a special claim on salvation.

And that’s a story.

-

Ammon is mentioned in forty-six chapters; Moab is also mentioned in twenty-two of those. It doesn’t work the other way around, though. Moab is found in sixty-four chapters, so about two-thirds of Moab’s mentions are solo. ↩

-

The Ammonites called them Zamzummim, which is a great name that sounds like it came from Dr. Seuss, not the author of Genesis. ↩

-

It’s possible that this is the style of house where Jesus was born. In this hypothesis, the “inn” is the guest rooms at the back, the “stable” is the front of the house with the animals, and the “manger” is the hollow in the floor where the animals were fed. See Kenneth Bailey’s Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes, pp. 28–30. ↩

-

Modern-day Amman in Jordan. ↩

-

This prophecy, gruesome as it is, forms part of a series of oracles in Amos that are all examples of Graded Numerical Paralellism. ↩

-

Judas Maccabeus defeated some people called “Ammonites” in the 160s BC, but given the Babylonian conquest, it’s unlikely they are the same nation despite living in the same place. ↩

-

So why did Matthew leave her out? The natural answer—”because she’s not a Jew”—doesn’t work, because he includes Ruth, who is not a Jew. I have a guess, but it’s just a guess.

The other women in Matthew 1 are all countercultural somehow: Tamar committed adultery with Judah; Ruth is a Moabite; Bathsheba committed adultery with David; and Mary had a child without a husband. So we have three Jewish sexual outcasts and a foreigner who famously claims Yahweh as her own. Naamah, on the other hand, was an unrepentant worshiper of Milcom/Molech who drew Solomon into idolatry.

While we are all sinners, including every person in Jesus’s ancestry, a good writer doesn’t turn his readers away in the first chapter, and Matthew wisely leaves Naamah out. ↩

This post is part of the series “King Jehoshaphat's Prayer”

-

King Jehoshaphat’s Prayer: A Scriptural Response to Fear

-

Who Was Jehoshaphat Anyway?

-

From Sodom and Gomorrah to Jesus: The Story of the Moabites

-

Sitting In the Shadows of History: The Story of the Ammonites 👈 you are here

-

Everywhere and Nowhere: The Story of the Amalekites