Praise the Lord!

Praise the name of the Lord,

give praise, O servants of the Lord,

who stand in the house of the Lord,

in the courts of the house of our God!

Four times in two verses, the name of the Lord comes to the lips of the psalmist. The repetition sets up a rhythm that sometimes eludes the translators of the psalms.

These poems—and they are poems—run into two translation problems, especially for modern readers of English.

The first is the normal one: translating Hebrew to English is simply not easy. Not because either is a particularly hard language. Hebrew is actually among the simpler languages out there, although that can create its own problems when an author needs to use a simple language to express complex truths of God.

Any translation effort is a big deal, and when you’re working with the Word of God, there’s kind of a lot riding on getting it right. You wouldn’t want to accidentally mislead potentially millions of Christians into thinking the wrong thing because you didn’t work quite hard enough.

There’s a somewhat famous example of exactly this happening. In 1631, a pair of printers named Robert Barker and Martin Lucas went to reprint the King James Bible. The KJV was a smash success, being not only a widely available English Bible but also, you know, approved by the king! It could be… unhealthy… to have an unapproved Bible in that time.

So these two went to press. I’m not an expert in early printing techniques, but I doubt they just brought up InDesign and clicked Print. They had to manually set out every letter of every word of every page—backward!—along with spaces and leading (the space between the lines) and every other feature they wanted to print. For every single page. For the whole Bible. This was a massive work.

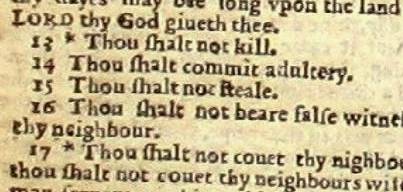

Anyway, in the middle of the hundreds of thousands of words painstakingly set by hand, they accidentally left one out. A short one, but kind of an important one. Here’s Exodus 20:14, the seventh commandment, from their version of the KJV. See if you can spot the error:

Here it is in print, in case you missed it:

Thou shalt commit adultery.

Yes, they left out the word “not” between “Thou shalt” and “commit adultery.”

As a result, they were fined £300 (almost $60,000 in 2018) and had their printing license revoked, which was bad enough. But also, this version is known as “the Wicked Bible” for the rest of time, which seems worse.

I know that’s not really a translation error, and I suspect few people were fooled into thinking God suddenly condoned extramarital affairs, but I love that story, and also it suggests that modern Bible editors have to be perfect. Any mistake can lead people down a disastrous road, especially if it’s the only Bible they have.

So translation is hard. But poetry translation is even harder, because you not only have to figure out how to translate words and phrases, but also rhythm and rhyme and imagery.

On the plus side, ancient Hebrew poetry wasn’t really big on rhyme (for that matter, neither was ancient English poetry), so that makes some things easier.

But they loved structured repetition of sounds or syllables or words or phrases, and you can kind of get a sense of that here.

PRAISE the Lord!

PRAISE the name of the Lord,

give PRAISE, O servants of the Lord,

who stand -in the house- of the Lord,

-in the courts of the house- of our God!

See the intense, overlapping repetition in just five lines?

We see “praise” three times, “of the Lord” four times and “of our God” once, and “in the house” followed by “in the courts of the house.”

That’s the result of a careful translator who not only knows ancient Hebrew but also understands how ancient Hebrew poetry worked. He doesn’t try to make the lines rhyme, because they’re not supposed to (it would kind of be cheating to rhyme “Lord” with “Lord” anyway).

There’s one more translation aspect—cultural translation—that doesn’t necessarily crop up here. Sometimes we simply don’t understand the ancient people we’re reading about, and the translator has to decide whether to accurately translate the text, which might leave her readers confused, or accurately translate the culture, which inserts her between the text and the readers—a precarious position when dealing with the Word of God.

So translation is hard work. And this idea of word choice brings us back to what caught my attention in the first place, this glorious repetition of the name of the Lord.

Do you know, or remember, that God has a name? Like an actual name?

Learning this is a bit like learning that your dad has a first name. You’ve called him “Dad” your entire life. In my family at least, my mother also referred to him as “Dad” when talking to me (and vice-versa: it was always “go ask Mom whether you can go outside”).

And then some time when you’re eight you’re with him and he meets a friend and the friend calls him by his first name: “Chip1, good to see you again.”

Who’s… Chip?

I mean, I know people have names. We don’t live in Calvin and Hobbes where the parents are only ever “Mom” and “Dad”. I know they have real names. I’ve just… never thought about it before.

Well, God has a name. Generations of people knew Him, followed Him, walked with Him, and (as far as we know) never knew His name. It seems even Adam and Eve didn’t know His name, which is weird because they literally walked with Him, but if they had, they’d have told Seth, and Seth would have told Enosh, and a zillion years later Moses wouldn’t have had to ask, “So, um, what do I say, when they look at me like I’m crazy and ask who sent me?” (Exodus 3:13)

But he did have to ask, and I’m glad he did, because we know our God has a personal name:

I AM WHO I AM

That’s… okay, the translator is just messing with us. That’s not a name. Let’s just check the Hebrew real quick, and…

אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה

Um, okay, that’s not really helpful. I promise it’s not really that helpful even if you can read Hebrew. And worse, if you’re really paying attention, that’s not the name of God. Here’s the name, later called the “Tetragrammaton” because it’s four Hebrew characters:

יהוה

See, those are similar but not identical. This second version is the one we spell “Yahweh” in English; the word from Exodus is usually spelled “Ehyeh.”

At this point, I’d love to wander off into a discussion of the name of God and all the weirdness about this particular exchange with Moses2, but for today I want to get back to this psalm, where the poet uses two different versions of the name of God, which this translator decided to smush into “the LORD” in both cases.

In the first line, “Praise the Lord!”, the poet uses kind of a short form of the name, יה, pronounced “Yah” (or “Jah”, if you remember that “j” is pronounced like a “y” unless you’re Bob Marley).

Then he switches back to the full name Yahweh until verse 3, when again he uses Jah the first time and Yahweh the second.

This is kind of like using “Matt” sometimes and “Matthew” other times, and it helps break up the monotony of using the same word over and over again even when the whole point is using the same name over and over again.

The psalmist calls on us to praise the name of the Lord, and then he uses His name over and over again to drive home the point. It is the name of the Lord, this personal God, this familiar creator, whom we are called to praise and worship.

God is not distant, even to the ancient Hebrews. This is the God who walked with Adam and Eve and Enoch, who appeared as a man to Abraham and as a cloud and a pillar of fire to Israel, who showed his back side to Moses and spoke to Elijah in a still small voice. He is a God of the mountaintop, to be sure, but He is also a God who comes to rest in the midst of the camp.

As Christians, God is even less distant: His Son, His very self, He sent as a man—not the appearance of a man, like Abraham saw—to live and die and be raised for our salvation. And closer still, His Spirit lives and works and breathes inside us, part of our being.

The psalmist didn’t know this last part, but he knew that his God was special among all the gods. He spends a good chunk of the rest of the psalm on the history of Israel, reminding us of just who this Jah fellow is and why we should praise Him. He also mentions other gods, and how they are not weak but dead, not mute but nonexistent. If we were to praise them, he says, we would become like them (Psalm 135:18).

But we worship the true God, the one whose name we know, whose house we enter, the living God. And—by implication—we will become like Him, alive beyond life.

Pretty amazing theology from someone living so far before Jesus. And all because of the name.

-

My real dad’s real name. His birth certificate says Oscar, but everyone else says Chip. I still say “Dad”, of course. ↩

-

Okay, I can’t help it. In brief, some scholars think that Moses asked God’s name because he had grown up outside Israelite culture and then run away, so he didn’t know God’s name, but the “real” Israelites did, and it would be like a password to prove the God he talked to was in fact the God of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob. ↩