SummaryPermalink

In ancient Israelite culture, the firstborn typically inherited leadership, wealth, and responsibility within the family. However, Judah—Jacob’s fourth-born son—unexpectedly rose to prominence over his elder brothers Reuben, Simeon, and Levi, becoming the ancestor of King David and ultimately Jesus Christ. This surprising shift highlights God’s sovereign choice and challenges human assumptions about worthiness, inheritance, and leadership. Exploring Judah’s ascent reveals God’s character: He frequently selects the overlooked, the repentant, and even the scandalous to fulfill His purposes. Understanding these divine choices enriches our delight in Scripture, inviting us to read the Bible not merely as historical narrative but as a transformative revelation of God’s grace and redemption.

I. Introduction: The Importance of Birthright and BlessingPermalink

In ancient Israel, the concept of birthright was central to family dynamics, inheritance, and spiritual leadership. Traditionally, the birthright belonged to the eldest son, granting him a double portion of the inheritance and placing upon him the responsibility of family leadership. This expectation, codified later in Israelite law, is vividly stated in Deuteronomy:

but he shall acknowledge the firstborn, the son of the unloved, by giving him a double portion of all that he has, for he is the firstfruits of his strength. The right of the firstborn is his.

—Deuteronomy 21:17

This greater share represented more than mere economic advantage; it embodied substantial responsibilities. The eldest son was expected to care for the extended family’s welfare, protect its members, and maintain justice and harmony. A clear example is found in Abraham, who mobilized his household to rescue his nephew Lot during the war between the five kings and the four kings (Genesis 14:13–16). Abraham’s extensive inheritance enabled him to act decisively in fulfilling his family obligations.

While the birthright traditionally passed automatically to the eldest son, Scripture presents several instances where this inheritance was either willingly exchanged or deliberately redirected. Esau famously traded his birthright to his younger brother Jacob in a moment of hunger and shortsightedness (Genesis 25:31–34). Later, Jacob himself deliberately modified the expected order of inheritance when blessing Joseph’s sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, placing the younger Ephraim above the older Manasseh (Genesis 48:13–20).

Inheritance typically excluded women, as daughters generally joined their husband’s families upon marriage. However, Scripture records notable exceptions. The daughters of Zelophehad successfully petitioned Moses (and God Himself), establishing a precedent allowing daughters to inherit if there were no sons (Numbers 27:1–11). This progressive decision hinted at the broader inclusivity and grace characteristic of God’s unfolding kingdom. Jesus himself reinforced a unique perspective on family unity, emphasizing that marriage creates a new household rather than simply absorbing a wife into her husband’s lineage (Matthew 19:5).

Within Jacob’s family, birth order carried heightened significance due to the intense rivalry between his two wives, Leah and Rachel. Both women sought to bear numerous sons, each hoping to secure inheritance and prominence for her descendants. Leah’s initial pride in bearing Jacob’s first sons exacerbated ongoing tensions, making birth order crucial within their already complex household.

Despite these entrenched cultural expectations, Scripture presents a striking anomaly: Judah, Jacob’s fourth-born son, emerges as the forefather of both King David and ultimately Jesus Christ. The three eldest brothers—Reuben, Simeon, and Levi—are all bypassed. This unexpected shift prompts the critical question: why Judah?

Scripture explicitly acknowledges this surprising turn of events:

“The sons of Reuben the firstborn of Israel (for he was the firstborn, but because he defiled his father’s couch, his birthright was given to the sons of Joseph the son of Israel, so that he could not be enrolled as the oldest son; though Judah became strong among his brothers and a chief came from him, yet the birthright belonged to Joseph).”

—1 Chronicles 5:1–2

This passage clarifies a crucial distinction: while Joseph received the economic advantages of the birthright through his sons, leadership and prominence passed specifically to Judah. Investigating how and why this occurred deepens our appreciation of God’s sovereignty and offers insight into broader biblical patterns, ultimately enriching our delight in exploring the profound truths interwoven throughout Scripture.

This introduction sets the stage for a careful, detailed exploration across subsequent sections, each building toward a deeper understanding of God’s unexpected choices—highlighting both their theological significance and practical implications for us today.

II. Jacob’s Sons and the Original HierarchyPermalink

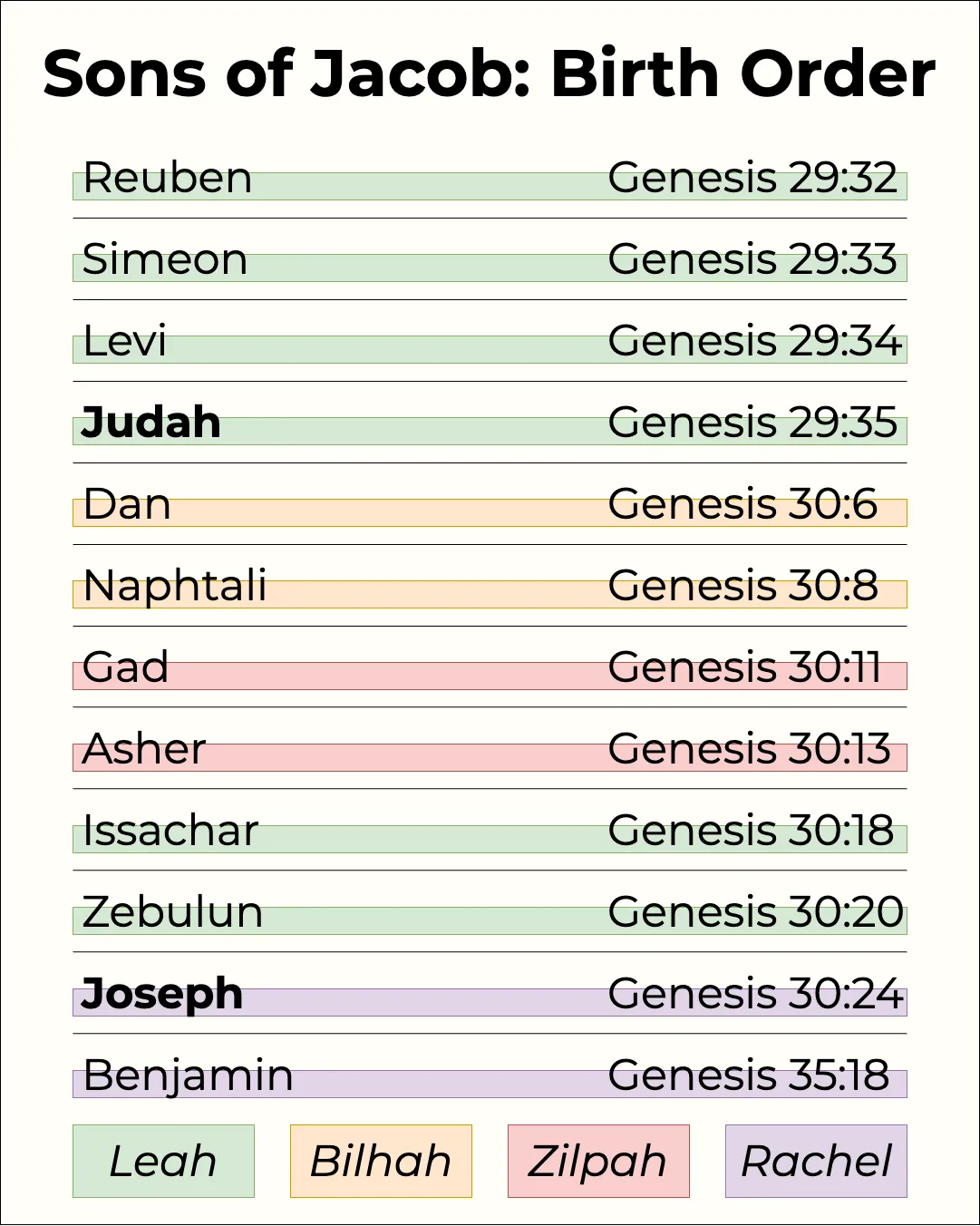

To understand fully why Judah, Jacob’s fourth-born son, emerged as the family leader, it’s essential to first clearly outline the original birth order of Jacob’s twelve sons. Scripture lists these sons in varying sequences across both Old and New Testaments—often adjusting the order or omitting certain individuals for narrative or thematic reasons. The most straightforward account of their literal birth order and maternal lineage appears clearly in Genesis 29–30 and Genesis 35:18:

| Order | Name | Mother | Verse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reuben | Leah | Genesis 29:32 |

| 2 | Simeon | Leah | Genesis 29:33 |

| 3 | Levi | Leah | Genesis 29:34 |

| 4 | Judah | Leah | Genesis 29:35 |

| 5 | Dan | Bilhah | Genesis 30:6 |

| 6 | Naphtali | Bilhah | Genesis 30:8 |

| 7 | Gad | Zilpah | Genesis 30:11 |

| 8 | Asher | Zilpah | Genesis 30:13 |

| 9 | Issachar | Leah | Genesis 30:18 |

| 10 | Zebulun | Leah | Genesis 30:20 |

| 11 | Joseph | Rachel | Genesis 30:24 |

| 12 | Benjamin | Rachel | Genesis 35:18 |

This table highlights an immediate complexity: Jacob’s sons were born to four different women. Such intricacy underscores the intense family drama and rivalry woven throughout the narrative of these patriarchs. Leah bore Jacob’s first four sons, giving her significant cultural leverage as the mother of the eldest—including the pivotal firstborn son, Reuben. Yet despite Leah’s remarkable fertility—something she attributed explicitly to God’s favor—Jacob’s affections notably favored Rachel, for whom he labored fourteen years, seven unwillingly married to Leah due to her father’s deceit.

Driven by intense jealousy and frustration at her infertility, Rachel adopted a cultural solution that mirrored the earlier decision of Abraham’s wife, Sarah: she gave her servant Bilhah to Jacob, hoping to bear children through her (Genesis 30:3). Although biologically Bilhah’s children, Dan and Naphtali were considered culturally Rachel’s. In response, Leah similarly offered Jacob her own servant, Zilpah, resulting in two more sons, Gad and Asher.

Thus began a tense, competitive atmosphere between the sisters, each striving for dominance through childbearing. Leah later conceived two additional sons herself—Issachar and Zebulun—thus securing her family position further. By this point, Leah culturally possessed eight of Jacob’s sons, while Rachel, through Bilhah, had only two.

Eventually, God intervened compassionately in Rachel’s story, blessing her with Joseph, who rapidly became Jacob’s clear favorite (Genesis 37:3). This favoritism triggered profound sibling rivalry, ultimately leading to Joseph’s sale into slavery and Israel’s eventual sojourn in Egypt. Later, Rachel gave birth to Benjamin, another deeply beloved child of Jacob’s old age.

Grasping this complicated familial web is crucial, as each son’s standing shaped their expectations of inheritance, authority, and divine favor. Typically, the firstborn held a culturally and spiritually privileged position, as vividly demonstrated by the story of Jacob and Esau (Genesis 25:31–34). However, God’s narrative frequently subverts these expected cultural norms, choosing individuals in surprising ways to reveal His sovereignty and grace. Judah’s unexpected rise illustrates this consistent biblical theme, offering profound insights that enrich our appreciation and delight in Scripture.

III. The Fall of Reuben (The Firstborn)Permalink

Reuben, Jacob’s firstborn son, was poised by birth to inherit the greatest honor and responsibility within the family. Yet tragically, he was also the first to lose this privileged position. Scripture identifies two primary reasons for Reuben’s fall: first, a serious sin of adultery and disrespect, and second, an abdication or failure in fulfilling the responsibilities expected of the eldest son.

Reuben’s downward spiral began dramatically and explicitly when he slept with Bilhah, Rachel’s servant and Jacob’s concubine. Genesis records the event plainly:

“While Israel [Jacob] lived in that land, Reuben went and lay with Bilhah his father’s concubine. And Israel heard of it.”

—Genesis 35:22

In committing this act, Reuben transgressed in two severe ways. First, Reuben committed adultery, violating the standards later articulated explicitly in Leviticus 18:8, which prohibited relationships with a father’s wife. Second—and perhaps even more gravely—Reuben’s action was inherently incestuous by the familial standards later clearly outlined in Leviticus 18:7, since Bilhah held a maternal role within the family. Thus, Reuben’s transgression was not merely moral, but profoundly disrespectful to his father and to the sanctity of their family structure.

Reuben’s action can also be understood through the lens of inheritance itself. Upon Jacob’s death, all his possessions—including his concubines—would traditionally pass to the eldest son. Reuben, through impatience and presumption, prematurely attempted to claim what he saw as already rightfully his. This scenario parallels the well-known parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32), who similarly demanded his inheritance prematurely, essentially communicating to his father, “I wish you were already dead.” The prodigal son’s story ultimately highlights God’s extravagant mercy, forgiveness, and redemption. In contrast, Reuben’s story serves as a cautionary tale of impatience, presumption, and profound disrespect. Reuben’s sin included not just adultery and incest, but also implicitly a rejection and disrespect of his father’s rightful authority and life itself—making his sin a threefold failure of morality, honor, and familial duty.

Scripture explicitly confirms Reuben’s loss of the birthright. Jacob himself proclaimed this loss in his prophetic blessing:

“Unstable as water, you shall not have preeminence, because you went up to your father’s bed; then you defiled it—he went up to my couch!”

—Genesis 49:4

Centuries later, the Chronicler explicitly reinforces Reuben’s demotion, affirming that this sin decisively cost him the birthright:

“The sons of Reuben the firstborn of Israel (for he was the firstborn, but because he defiled his father’s couch, his birthright was given to the sons of Joseph the son of Israel, so that he could not be enrolled as the oldest son).”

—1 Chronicles 5:1

But sin is not merely theological; it carries tangible consequences within relationships and leadership. Reuben’s failure directly affected his credibility among his brothers, weakening his influence at a critical moment. In Genesis 37, when the brothers plotted against Joseph, Reuben attempted a subtle act of leadership: suggesting they throw Joseph into a pit rather than kill him outright, intending secretly to rescue him later (Genesis 37:21–22). Yet, his weakened authority was evident—Judah quickly stepped into the leadership vacuum, proposing an alternate plan to sell Joseph to passing Ishmaelites (Genesis 37:26–27). Reuben’s diminished standing set the stage for Judah’s rise to prominence, ultimately reshaping the trajectory of Jacob’s family.

Jacob, undoubtedly wounded by Reuben’s betrayal, would have distanced himself emotionally, further eroding Reuben’s authority. Later narratives reinforce Judah’s increasing leadership, as Judah—not Reuben—represented the brothers before Jacob (Genesis 43:3), Joseph (Genesis 44:14), and during the critical relocation to Egypt (Genesis 46:28).

Reuben’s story underscores more than historical curiosity. It illustrates clearly how moral choices and relational integrity profoundly impact leadership and legacy. Scripture does not shy away from showcasing human weakness, reminding readers that even prominent figures have profound flaws. By exploring these complexities openly, Scripture enriches our understanding of God’s sovereignty and grace, inviting deeper reflection and delight in His redemptive plans.

IV. Simeon and Levi: Instruments of ViolencePermalink

With Reuben’s loss of birthright, leadership and inheritance should naturally have passed next to Simeon, Jacob’s second-born. However, in one decisive and violent act, Simeon and Levi jointly forfeited their privileged positions. Their story is troubling, yet it begins with an arguably honorable motive: defending their sister, Dinah.

Dinah, Jacob’s only explicitly named daughter, was Leah’s child. Tragically, Dinah was abducted and raped by Shechem, the son of Hamor, a local Hivite ruler. Following his crime, Shechem ironically expressed a desire to marry Dinah. Hamor approached Jacob with a proposal, seeing this as a strategic alliance—an opportunity to integrate Jacob’s prosperous household into their community (Genesis 34).

Jacob’s sons, primarily Simeon and Levi, responded with calculated deceit. They agreed to the marriage only on condition that all the men of Shechem’s city undergo circumcision, the sacred covenantal sign between God and Abraham (Genesis 17:10). Trusting in this deceitful agreement, Hamor and Shechem convinced the city’s men to comply.

Exploiting the vulnerability of the Hivites’ recovery, Simeon and Levi executed a brutal plan: they attacked the city, killing all male inhabitants, including Hamor and Shechem, rescuing Dinah but also pillaging the city’s possessions and capturing the surviving women and children as spoils (Genesis 34:25–29).

While the outrage over Dinah’s violation was justified and demanded accountability, Simeon and Levi’s actions crossed critical boundaries, committing at least four profound sins:

First, they manipulated the sacred rite of circumcision, intended as a holy sign of God’s covenant, using it as a deceptive tool for vengeance (Genesis 34:13). This misuse profoundly dishonored God’s sacred commands.

Second, their retaliation far surpassed justice, resulting in the massacre of an entire community rather than punishing the individual responsible. Scripture implicitly contrasts their actions with God’s merciful willingness to spare Sodom if only ten righteous people could be found (Genesis 18:32). Simeon and Levi allowed no such restraint.

Third, they usurped God’s role as the righteous judge, explicitly defying a principle later articulated clearly in Deuteronomy and Romans:

Vengeance is mine, and recompense, for the time when their foot shall slip; for the day of their calamity is at hand, and their doom comes swiftly.’

—Deuteronomy 32:35

Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.”

—Romans 12:19

Their actions displaced God’s rightful authority.

Fourth, Simeon and Levi gravely dishonored their father Jacob, who explicitly rebuked them for jeopardizing the family’s safety and reputation in the land (Genesis 34:30).

These actions had lasting consequences. Jacob’s prophetic blessing later explicitly articulated their disqualification:

“Simeon and Levi are brothers; weapons of violence are their swords.

Let my soul come not into their council; O my glory, be not joined to their company.

For in their anger they killed men, and in their willfulness they hamstrung oxen.

Cursed be their anger, for it is fierce, and their wrath, for it is cruel!

I will divide them in Jacob and scatter them in Israel.”

—Genesis 49:5–7

This prophetic curse permanently altered their legacy, scattering Simeon within Judah’s territory and assigning Levi’s descendants a priestly role without territorial inheritance. Reuben, Simeon, and Levi were thus all set aside, paving the way for Judah’s ascension.

While Simeon and Levi’s actions were reprehensible, we must also consider Jacob’s indecisive response, which left Dinah without proper justice and protection. This serves as a poignant reminder that only God’s justice is perfect, reliable, and truly righteous. Even amid dark human failure, Scripture points toward God’s ultimate redemptive justice in Christ, deepening our understanding and enriching our delight in His Word.

V. Judah: Emergence of a LeaderPermalink

With Reuben, Simeon, and Levi disqualified by their moral failures, Judah naturally emerged into a position of leadership. Importantly, Judah’s rise was not simply by default; instead, it was marked by deliberate actions and increasing authority recognized by his family.

Judah’s leadership was first evident during the incident involving Joseph. When the brothers plotted against their favored younger brother, Judah suggested selling Joseph to traders rather than killing him outright (Genesis 37:26–27). Although morally compromised, this suggestion demonstrated Judah’s practical influence and natural leadership capability among his brothers.

This influence grew notably stronger during the severe famine when the brothers travelled to Egypt. Judah boldly assumed responsibility, persuading their father Jacob to trust him with Benjamin’s safety during their second journey (Genesis 43:3–10). Judah’s decisive leadership contrasted sharply with Reuben’s earlier ineffective plea, clearly demonstrating his growing familial authority.

In Egypt, facing a disguised Joseph, Judah courageously stepped forward as the spokesperson, passionately pleading for Benjamin’s release in a moment of emotional vulnerability (Genesis 44:14–34). Judah’s heartfelt plea was pivotal, deeply affecting Joseph and ultimately leading to Joseph revealing his identity and reconciling with his brothers.

Later, when orchestrating the family’s relocation into Egypt, Jacob explicitly sent Judah ahead to lead the family into Goshen, formally acknowledging Judah’s leadership (Genesis 46:28).

Jacob’s prophetic blessing solidified Judah’s status, explicitly marking him as the family’s enduring leader:

“Judah, your brothers shall praise you…

The scepter shall not depart from Judah…

and to him shall be the obedience of the peoples.”

—Genesis 49:8–10

This prophetic blessing had profound implications, reaching far beyond Judah’s lifetime. King David, who unified Israel and expanded its territories, directly descended from Judah (Matthew 1:6). Ultimately, this lineage culminated in Jesus Christ, whose universal authority fulfills Jacob’s ancient prophecy. As Philippians 2:10–11 vividly declares, it is before Jesus—the descendant of Judah—that “every knee shall bow.” Revelation further confirms Jesus as the “Lion of the tribe of Judah,” emphasizing Judah’s lasting legacy in God’s redemptive history (Revelation 5:5).

Thus, Judah’s emergence as leader not only illustrates God’s sovereign and gracious choice in the immediate context of Jacob’s family—it also becomes a vital thread woven through the tapestry of redemption. As we’ll see later, Judah undergoes his own redemption story, cementing his capacity for Godly leadership. Judah’s leadership points ultimately to Christ Himself, the perfect fulfillment of every biblical prophecy about kingship, leadership, and universal authority. Recognizing these deep, beautiful connections within Scripture can greatly enhance our understanding of God’s intricate plans and sovereignty, bringing deeper joy and delight to our exploration of His Word.

VI. Why Judah? Theological ReflectionsPermalink

Judah’s rise cannot be explained solely by family dynamics or default succession. His lineage includes Israel’s greatest earthly king—David—and the King of Kings, Jesus Christ. Behind this surprising elevation is something far greater than birth order: God’s sovereign will, unfolding with intention and grace.

Scripture is rich with examples of God bypassing conventional expectations. Judah’s father Jacob was himself a second-born who supplanted his older brother Esau, both in birthright and blessing. Later, Jacob crossed his arms to bless Ephraim over Manasseh, Joseph’s younger son over the elder (Genesis 48:13–20). When Samuel went to anoint a new king, God passed over David’s older brothers in favor of the youngest, a shepherd boy overlooked by his own father (1 Samuel 16:6–13). The pattern is consistent: God chooses not based on position, power, or pedigree, but on His purposes. As God reminded Samuel, “Man looks on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart” (1 Samuel 16:7).

Over and over, God chooses those the world overlooks. Not the oldest. Not the strongest. Not the most qualified by earthly standards. Saul looked like a king—tall, handsome, impressive—but he proved unfaithful and unrepentant. David, by contrast, became Israel’s greatest king not because of his stature, but because of his heart for God. And so it is with Judah. He was not the eldest, nor the favored son of the favored wife. He was Leah’s fourth son—born to the wife Jacob had not even meant to marry. Yet God chose Judah. His choosing does not mirror ours.

This divine pattern continues in Judah’s personal story as well. Like his brothers, Judah was not perfect. In fact, he was the very one who first suggested selling Joseph to the Ishmaelites (Genesis 37:26–27), an act of betrayal with devastating consequences. So why does Judah’s sin not disqualify him, as Reuben’s or Simeon’s did?

The answer lies in what Judah does next.

Perhaps the clearest example of Judah’s transformation comes in Genesis 38, a deeply uncomfortable chapter in which Judah’s moral failure is on full display. His eldest son, Er, marries Tamar, but is struck dead by God for his wickedness. Following the law of levirate marriage, Judah instructs his second son, Onan, to marry Tamar and provide offspring on Er’s behalf. Onan refuses—seeking to preserve his own inheritance—and is also struck down by God. Rather than fulfill his duty by giving Tamar his third son, Shelah, Judah delays. He leaves her waiting in shame.

But Tamar, clever and courageous, devises a plan. Disguising herself as a prostitute, she tricks Judah into sleeping with her. When she later reveals she is pregnant by him, Judah—publicly shamed and morally exposed—does something extraordinary. He does not deflect or deny. He does not blame her. He says, “She is more righteous than I” (Genesis 38:26). In that moment, Judah repents. He acknowledges not only the act itself but the injustice he committed against her. He takes responsibility. He accepts Tamar, and the twins she bears—Perez and Zerah—as his own.

Judah’s repentance is the turning point. Unlike Reuben, who never seems to confess or restore what was lost, Judah owns his sin and acts to make it right. His repentance reflects a heart sensitive to truth, willing to change, and eager to do justice. And in this, Judah anticipates David—who, when confronted by the prophet Nathan for his sin with Bathsheba and the murder of Uriah, breaks down in sorrow and writes Psalm 51, pleading, “Create in me a clean heart, O God.”

This repentance set Judah apart. Unlike Reuben, who faltered and faded, or Simeon and Levi, whose rage consumed them, Judah took responsibility. He changed. He grew. Later, he would offer himself as a substitute for Benjamin (Genesis 44:33), foreshadowing the self-sacrifice that would characterize his most famous descendant.

Judah’s story reminds us that God does not demand perfection. He honors humility, repentance, and transformation. This is the essence of God’s grace: choosing the imperfect and shaping them for His purposes. The lineage of Christ flows not through spotless heroes but through the flawed and the forgiven—through people like Judah.

VII. Broader Scriptural ImplicationsPermalink

God’s choice of Judah—a fourth-born son of a wife Jacob never meant to marry—fits a broader and beautiful biblical pattern. As we’ve seen, God’s sovereignty frequently overturns cultural expectations, favoring second sons over firstborns, the overlooked over the obvious, and the repentant over the perfect. But this divine reversal extends well beyond the story of inheritance. Throughout Scripture, God seems to delight in choosing the most unexpected people to carry out His most important work.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the genealogy of Jesus recorded in Matthew 1. Far from presenting a pristine lineage of perfect patriarchs, Matthew highlights a lineage that includes deeply flawed men and women—each one carefully chosen, each one placed with divine purpose.

Take, for example, the four women included in this genealogy. Their presence alone is striking. In ancient times, genealogies focused entirely on male descendants, tracing authority and inheritance from father to son. Including even one woman would have been unconventional. Including four was revolutionary.

The first is Tamar, Judah’s daughter-in-law, whose story we’ve already explored. After being mistreated, overlooked, and left childless, Tamar dresses as a prostitute and tricks Judah into sleeping with her. But in the end, Judah confesses, “She is more righteous than I.” Her child Perez, the second-born of twins, becomes the one through whom the line of Jesus continues.

Next is Rahab, an actual prostitute from Jericho. She bravely hides Israelite spies and helps them escape during Joshua’s conquest of the city. In return, she and her household are spared. Rahab marries into Israel and becomes the mother of Boaz.

Boaz, in turn, marries Ruth, a Moabite foreigner. According to Mosaic law, Moabites were excluded from Israel’s assembly (Deuteronomy 23:3). Yet Ruth’s loyalty, kindness, and courage lead her into Israel’s story. Her union with Boaz produces Obed, the grandfather of David, Israel’s greatest king.

Then there is Bathsheba, described in Matthew’s genealogy as “the wife of Uriah.” Her relationship with David began in adultery and resulted in Uriah’s death. And yet, it was Bathsheba’s son, Solomon, who succeeded David and continued the line that would eventually lead to Jesus.

And finally, there is Mary, the young, unmarried woman from Nazareth who bore the Son of God. Mary had none of the scandal of the other women, but she too was unlikely—a poor woman from an insignificant town, chosen to bear the Messiah.

Each of these women represents a break with tradition. None of them “fit.” And yet all of them were chosen. Their stories form a theology of grace: God does not require perfection—He transforms the humble and honors the faithful. As Paul writes in Galatians,

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

—Galatians 3:28

The men in this genealogy are no better. Abraham lied about his wife. Jacob deceived his father. David committed murder. Solomon worshiped foreign gods. Rehoboam split the kingdom. If Scripture were merely a record of moral heroes, these men would not be in it. But as Paul writes:

“God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise;

God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong;

God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not,

to bring to nothing things that are,

so that no human being might boast in the presence of God.”

—1 Corinthians 1:27–29

Mary understood as well, singing in the Magnificat,

52 he has brought down the mighty from their thrones and exalted those of humble estate; 53 he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty. —Luke 1:52–53

God’s pattern is clear. He chooses not the impressive, but the humble. Not the righteous, but the repentant. Not the strong, but the willing.

And so we return to Judah. His story, so full of failure and repentance, becomes part of something unimaginably greater. Though centuries pass, Judah’s name is not forgotten. His story doesn’t fade into the background. Instead, it is stamped into eternity in the very throne room of God.

In Revelation 5, John weeps because no one is found worthy to open the scroll—until one of the elders comforts him:

“Weep no more; behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals.”

—Revelation 5:5

Even in heaven, Jesus is called not just the Son of God, but the Lion of the tribe of Judah. This title ties back across thousands of years, through Jacob’s blessing in Genesis 49, through David’s reign, through Tamar’s scandal, all the way to the moment when Judah repented and said, “She is more righteous than I.”

This is the God we serve—a God who redeems, who elevates the lowly, who delights to work through the unexpected. And when we read Scripture with eyes open to these patterns—when we trace Judah’s thread from Genesis to Revelation—we find not just information, but transformation. We see the character of a God who chooses the weak to show His strength. And in seeing Him more clearly, we are drawn deeper into joy and delight. Delight comes not just from understanding how Scripture works, but from seeing how it reveals the heart of God.

VIII. Practical Applications for TodayPermalink

The story of Judah—woven through jealousy and injustice, repentance and redemption—offers more than a lesson in family dynamics or inheritance customs. It speaks directly to our lives today. Beneath the surface of tribal history lies a deep well of theology, hope, and invitation. We are not just reading about what God did once—we are discovering who God is, and how He continues to work in the world and in us.

A. God’s Sovereignty in Our Lives—Choosing and Redeeming the UnlikelyPermalink

8 For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, declares the LORD. 9 For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts.

—Isaiah 55:8–9

God’s sovereignty is not a distant theological abstraction—it is the foundation of our trust, our hope, and, ultimately, our joy. As the psalmist writes, “Our God is in the heavens; he does all that he pleases” (Psalm 115:3). He is not subject to the approval of kings or prophets, to the expectations of tradition or culture, or even to our own sense of justice. He is entirely, magnificently free—and in that freedom, He chooses.

But His choices often baffle us. Why Judah? Why Tamar? Why Ruth, Rahab, David, Mary? Why the fourth son of a second son? At the time, no one could have guessed what God was doing. But when Samuel poured oil over the young shepherd David’s head, when Jesus was born in Bethlehem, when the lion of the tribe of Judah appeared in John’s vision in Revelation—suddenly it all snapped into place. The providence of God, scattered like stars across the sky, came into brilliant constellation.

I’ve seen this in my own life, too. I don’t always sense God in the moment. I’ve known people who talk about hearing from the Spirit in every small decision. That’s not usually my experience. But over years and seasons, when I reflect, I see God’s fingerprints: a conversation that opened a door; a setback that redirected my course; a move from Virginia, where I had community, to Texas, where I had none—but where He built something new. God rarely draws me a map. But in hindsight, I can trace His hand.

Where might you see God’s fingerprints, not in the moment, but in the years?

23 The steps of a man are established by the LORD, when he delights in his way; 24 though he fall, he shall not be cast headlong, for the LORD upholds his hand.

—Psalms 37:23–24

And if this is true, then it must also change how we treat others. Would we have welcomed Tamar? Or would we have condemned her for deceit and presumed sexual sin? Would we have made space for Rahab, a foreign prostitute? Would we have trusted Ruth, a Moabite? God did. He saw something no one else could see. So we must learn not to judge by appearance or assumption but to treat everyone as beloved children of God—because they are.

B. Repentance and Humility, Judah’s Hallmarks of LeadershipPermalink

As baffling as God’s choices can be, what’s even harder to grasp sometimes is our own behavior. Like David, we often don’t realize the damage we’ve done until someone lovingly holds up a mirror. God, in His grace, gives us that moment of clarity through what John Wesley called convicting grace—the nudge of the Spirit that opens our eyes to sin, that helps us see what we’ve become and how far we’ve wandered.

Judah had that moment with Tamar. David had it with Nathan. We can have it too. The question is, when it comes—will we resist it? Justify it? Or will we respond in humility, confess, and turn back to the God who never stopped pursuing us? Repentance isn’t just for the pious or the penitent. It’s the door to leadership, restoration, and joy. Maybe—just maybe—your act of repentance will ripple across generations, just as Judah’s did.

C. God’s Redemption Includes the Deeply FlawedPermalink

And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose.

—Romans 8:28

If Judah’s story does not disqualify him from God’s plan, then there is hope for all of us.

Judah sold his brother. Abandoned his daughter-in-law. Slept with her unknowingly. And yet—through repentance and restoration—God made him the father of kings. The ancestor of Jesus. The namesake of the Lion.

You are not beyond God’s reach. Your story is not too messy. Your mistakes are not too deep. If God can redeem Judah, He can redeem you. And not just forgive—but restore. Transform. Entrust. Use.

The redemptive arc of Judah’s life invites us to stop disqualifying ourselves and start trusting the grace that welcomes us in, calls us higher, and sends us out.

And I am sure of this, that he who began a good work in you will bring it to completion at the day of Jesus Christ.

—Philippians 1:6

D. How Deeper Understanding Becomes DelightPermalink

And finally, this is what brings us back to delight.

Who would have thought that a story about tribal rankings, disqualifications, and ancient family politics could lead us here? Yet when we stop to look closer—when we don’t rush past the genealogies and the uncomfortable stories, but instead wrestle with them—we discover a richness that transforms our reading. A piece of Scripture that once seemed dry suddenly becomes alive with the character of God, the echoes of grace, and the fingerprints of Jesus.

This is the path to delight: to take what doesn’t make sense, what seems boring or confusing or even unjust, and ask questions. To wonder. To listen. To dig. And in that digging, to uncover the God who delights to be found.

IX. Conclusion: Embracing God’s Surprising ChoicesPermalink

What began as a simple question—why does Judah, and not Reuben, become the head of Jacob’s family?—has unfolded into a sweeping portrait of God’s character, human frailty, and divine grace.

We’ve learned what happened to Reuben, Simeon, and Levi—how each forfeited the rights of the firstborn through grievous failure. We’ve seen how Judah stepped into a vacuum of leadership not by default, but by growth, humility, and repentance. And beyond the family drama, we’ve glimpsed the heart of God—a God who consistently chooses the overlooked, the outcast, the unexpected: second sons and barren women, widows and prostitutes, Moabite foreigners and daughters-in-law in disguise.

In these choices, God reveals His character. And in these stories, we see ourselves—not always as Judah, the repentant leader, but sometimes as Reuben, or Simeon, or Levi: grasping, presumptive, or self-righteous. Yet Scripture invites us not just to see who we are but to become who we are called to be: people of repentance, people of mercy, people drawn ever deeper into God’s redemptive plan.

These choices aren’t random. They are not whims. God is not making the best of a bad situation. He is orchestrating beauty out of brokenness. His wisdom moves across centuries, through empires and households, to bring Jesus—the Lion of Judah—into the world at just the right time.

And this is what transforms Bible reading from duty to delight.

Because reading the Bible isn’t meant to be a chore. It’s not homework. It’s an invitation. Even the parts that feel insignificant, confusing, or strange—like genealogies and tribal rankings—are full of wonder when we lift our eyes to what God is doing. When we study stories like Judah’s, we begin to see not just ancient history, but eternal design. Not just facts, but faithfulness. Not just names, but the name above all names woven into every chapter.

For whatever was written in former days was written for our instruction, that through endurance and through the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope.

—Romans 15:4

This is where delight begins: not in already knowing everything, but in discovering that every question—every “Why Judah?”—can lead us to the heart of God.

So today, I invite you to approach Scripture with fresh curiosity. Ask questions. Chase down names. Wonder aloud. Why this person? Why this place? Why this path? Who are those others in Matthew’s genealogy—and why did he break them into sets of fourteen?

Open my eyes, that I may behold wondrous things out of your law.

—Psalms 119:18

So take up the Word. Ask the strange questions. Follow the quiet threads. And in doing so, may you come not only to know Scripture more deeply, but to delight in it—to encounter the God who hides glory in the folds of every chapter, and invites you, always, to come closer.

If the Lion of Judah can come from a story like this, what might God be writing in yours?