This is a story about a cookie.

Not just any cookie: a specific triangular cookie made of shortbread and filled with different flavors of jellies and jams. It’s called a hamantasch, and I didn’t know it existed until this week.

This week is special because sunset on February 25, 2021 in the Gregorian calendar (the one you’re probably used to) began 14 Adar, 5781 in the Hebrew calendar. And 14 Adar is the celebration of the Purim, and the story of Purim is wild.

Here’s an abbreviated version.

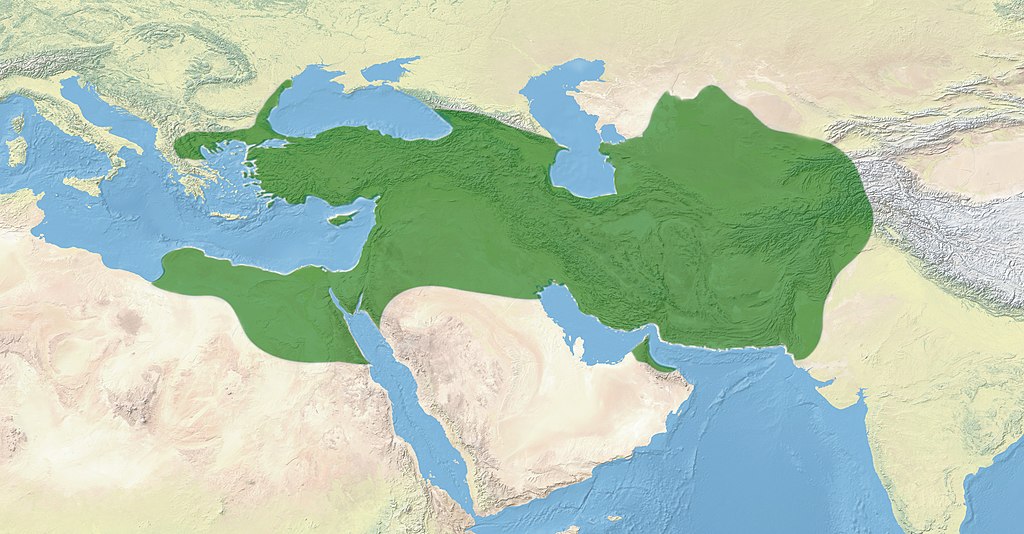

In the fifth century BC, Persia dominated the ancient world: from Egypt, Libya, and Macedonia in the west to India in the east, it was untouchable. In 486 BC, a new king came to power, Ahasuerus. Or as you might know him, Xerxes I.

The Book of Esther records an epic 180-day feast that Ahasuerus holds, during which he commands his queen, Vashti, to appear before his friends wearing nothing but her crown. She refuses, so Ahasuerus deposes her. He has beautiful women brought before him to choose a new queen, and he chooses Esther, a Jewish girl.

Meanwhile, Xerxes’s grand vizier, Haman, is plotting to rid the world of Jews. Well, not the world, just the empire—but the empire was so enormous, it pretty much encompassed all the Jews. He convinces Ahasuerus to issue an irrevocable edict allowing the genocide.

Esther’s relative Mordecai urges her to act with the famous words, “Who knows whether you have come to the kingdom for such a time as this?” (Esther 4:14) In response, she commands perhaps the bravest fast in Scripture: she asks the Jews to fast for three days for her and then declares that she will go before the king regardless of the result of the fast. Most people fast to listen for the will of God; not Esther—she’s going in. Her response is famous too: “If I perish, I perish.” (Esther 4:16)

Fortunately for the Jews, she convinces Ahasuerus to do two things. First, to issue a second edict permitting the Jews to defend themselves and plunder their attackers. And second, to hang Haman on a massive seventy-five-foot gallows he had prepared for Mordecai.

The Persians attack, the Jews defend, and the Jews win and plunder their enemies. With Ahasuerus’s permission, Esther declares a feast throughout the empire, and Jews still celebrate it today.

This is Purim.

Back to the CookiePermalink

What does all this have to do with the cookie? Well, despite the title of this post, it depends on who you ask.

- It might represent Haman’s legendary three-cornered hat. “What hat?” you ask, leafing back through Esther. Indeed, like God Almighty, Haman’s hat is not mentioned in the book of Esther. Nonetheless, it’s a popular theory.

- It might represent Haman’s pockets. “What pockets?” you ask, flipping through your Bible in disbelief. There’s at least a link here: tasch is Yiddish for pocket, and Haman offered Ahasuerus an enormous amount of money (ten thousand talents of silver, or about 750,000 pounds) to allow him to destroy the Jews (Esther 3:9).

- It might represent Haman’s ears. Before you go searching—no, his ears aren’t mentioned either. There’s not even a mention of whether his triangular ears are elven or Vulcan. Either way, the triangle might be a reference to cutting criminals’ ears in medieval times. This theory comes from the modern Hebrew term for these cookies, oznei haman, which literally means “Haman’s ears”.

- It might represent the Jewish attempt to keep kosher in the Persian empire. The most common filling for hamantaschen is honeyed poppy seeds (outside the U.S.; Americans apparently prefer jelly). When Daniel was abducted by Nebuchadnezzar, he requested seeds (modern English translations often say “vegetables”) instead of the king’s food to avoid disobeying God (Daniel 1:12).

- It might simply be named after the filling itself. The Yiddish word for those honeyed poppy seeds is mohn, so “honeyed poppy seed pockets” in Yiddish is mohntaschen, which sounds an awful lot like hamantaschen.

- It might be symbolic of God’s salvation. Just as, in the book of Esther, the name of God is never mentioned, but God’s providence shines through as clearly as any other Scripture, so the hamantaschen have a delicious center not visible from the outside1.

- It might represent the three-way power struggle among Ahasuerus, the Persian king; Esther, his Jewish queen; and Haman, his genocidal grand vizier. Along the same lines, it might represent the three patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

- Finally, it might be a reference to the way Mordecai alerted the Jews of the plot to kill them and the edict allowing them to fight back. There’s another legend, just like the hat, that to avoid discovery, Mordecai baked the new edict into pastries and distributed them that way, and the hamantaschen commemorate that clever concealment.

Regardless of what’s going on with the cookie, it reminds us today of one of the stranger books of the Bible, one that never mentions God, but is all about fasting, feasting, family, and faith.

P.S. If you’d like to make some of these for yourself, here are a bunch of hamantaschen recipes. If you make some, send me pictures on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook!

-

Here in Texas, we have the same thing, but we call them kolaches. I don’t think there’s a theological meaning behind kolaches, but most Texas consider them a religious experience. ↩