Read Your Bible Sideways

I do my daily devotionals on my phone pretty much all the time. It’s convenient, it’s always with me, and it helps me keep track of what I’m supposed to read that day.

It’s also pretty dumb.

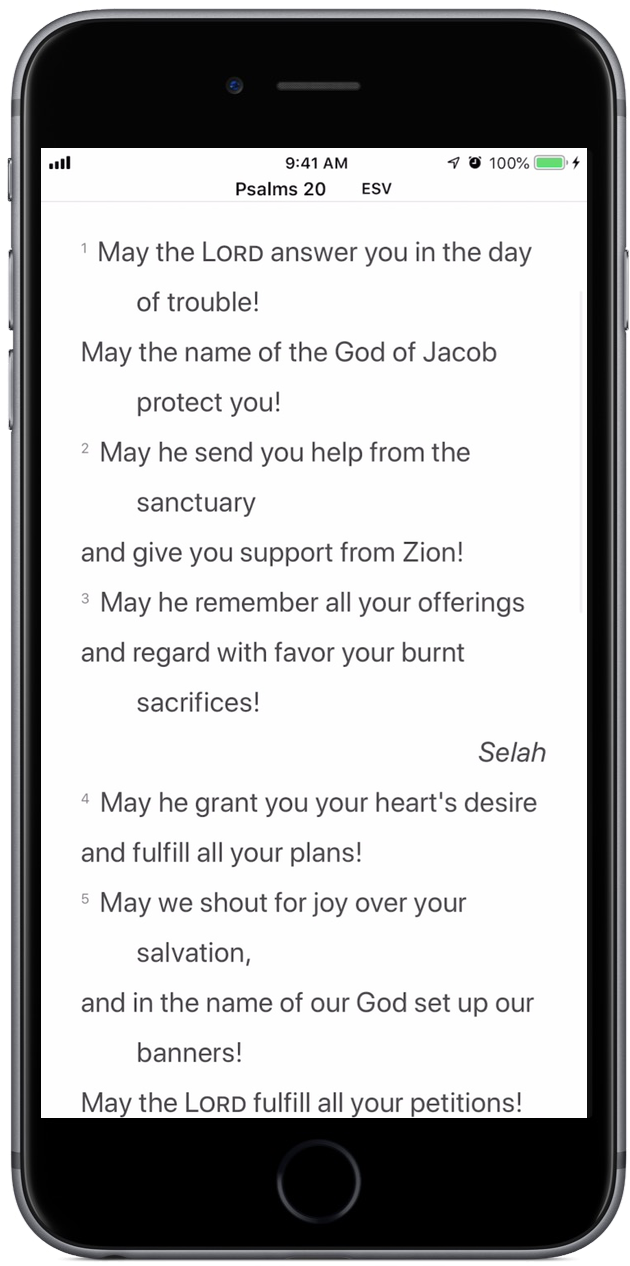

The phone, for all its computational power, has no idea what you’re reading. All it knows is that there are words and it should do its best to display them. So sometimes you end up with poetry that looks like this. Can you see what’s wrong?

The poet didn’t split his lines after “day”, “Jacob”, “the”, or “burnt”. He definitely didn’t try to emphasize “of trouble”, “protect you”, “sanctuary”, or “sacrifices” by setting them off by themselves.

But it sure looks like he did.

To be sure, this app1 tries to give you a hint by indenting the next line. But this is poetry. Real poetry, like Shakespeare or Pablo Neruda. Not just some words you feel obligated to read because they’re in the Bible.

Through A Filter, Darkly

To really engage with the Bible, to hear its voice as its authors intended, we need to recognize that we are reading through a number of filters:

- Inspiration. The Bible was inspired by the Holy Spirit, but written by men. While I believe that what got written down is what God intended to have written down, we are not reading the language of Heaven.

- Transcription. We do not have the original documents of the Bible, what scholars call autographs. Instead, we have copies of copies of copies. The best versions we have of the Bible are both more numerous and closer to the originals than almost all other ancient documents, but we still don’t have the originals. As a result, modern translations rely on comparing multiple copies of the same works to get the best possible result.

- Translation. Translating one language to another is challenging in the best of cases. Beyond just the syntax and the grammar and the definitions of individual words (consider, for example, the challenge of translating schadenfreude into English, or on fleek into… anything), all languages pick up idioms and poetry and imagery and sarcasm—and it’s not always obvious where one stops and another starts.

- Culture. Both the culture of the author and the culture of the reader come into play. The author records history or prophecy or poetry or wisdom in his own context, and doesn’t know what will or will not need explaining centuries in the future. The reader, disconnected now by thousands of years and unimaginable cultural changes, has her own context and reads in that light.

There are surely many other filters, and these explanations are drastically simplified, but these four stand out.

So what do we do about it? Two responses combine to give us confidence in what we read. First, remember how to read the Bible: start with prayer. Unlike every other book in the universe, the Bible has real power behind it, and God wants to touch your heart.

Second, remember that the Bible is said to be “twice-inspired”: the Holy Spirit was present when it was written, and He is present whenever it’s read. So He is active throughout the process, across all those years and miles and generations, and we trust Him to see us through.

But we can take action ourselves as well. For one thing, there are entire books to help you understand the cultures of the Bible, the languages of the Bible, the people and places and times of the Bible. But there are easier ways: just remove the barriers you see in front of you.

Barriers to Reading the Bible

Let’s look back at that screenshot and pick out all the things that aren’t original to it (beside the language; I’m sorry to inform you the Bible wasn’t originally English).

- Line endings. We already saw that we’re reading far more physical lines than the poet intended. Breaking up the visual structure makes the internal structure harder to see.

- Verse numbers. Verse numbers as we understand them were added during the 15th and 16th centuries, although various related systems have existed since the 900s. These divisions can help organize the text, but they are not God-inspired, and they can also hurt.

- Chapter numbers. Chapter numbers were added much earlier, around the 1200s AD. That’s still at least 1100 years after the books were written. Like verse numbers, they sometimes help, but a quick glance at Genesis 2 demonstrates they can also be confusing.

- Book titles. The English book titles we are familiar with came from various sources. For example, Genesis is named after the first word in the Latin version of Genesis. Psalms is named after a Greek word that means “instrumental music,” which is kind of funny for a book of lyrics. The Hebrew title for the book of Psalms translates to “praises”, which, frankly, would be a better title.

- Section headings. While not visible in most of the screenshots in this article, modern Bible translators like to insert section headings to help us understand and keep track of what we’re reading. I have found that these mostly hinder my comprehension rather than help, by spoon-feeding me instead of making me think. And, of course, they’re not original to the text, which means they’re not Scripture, helpful or not.

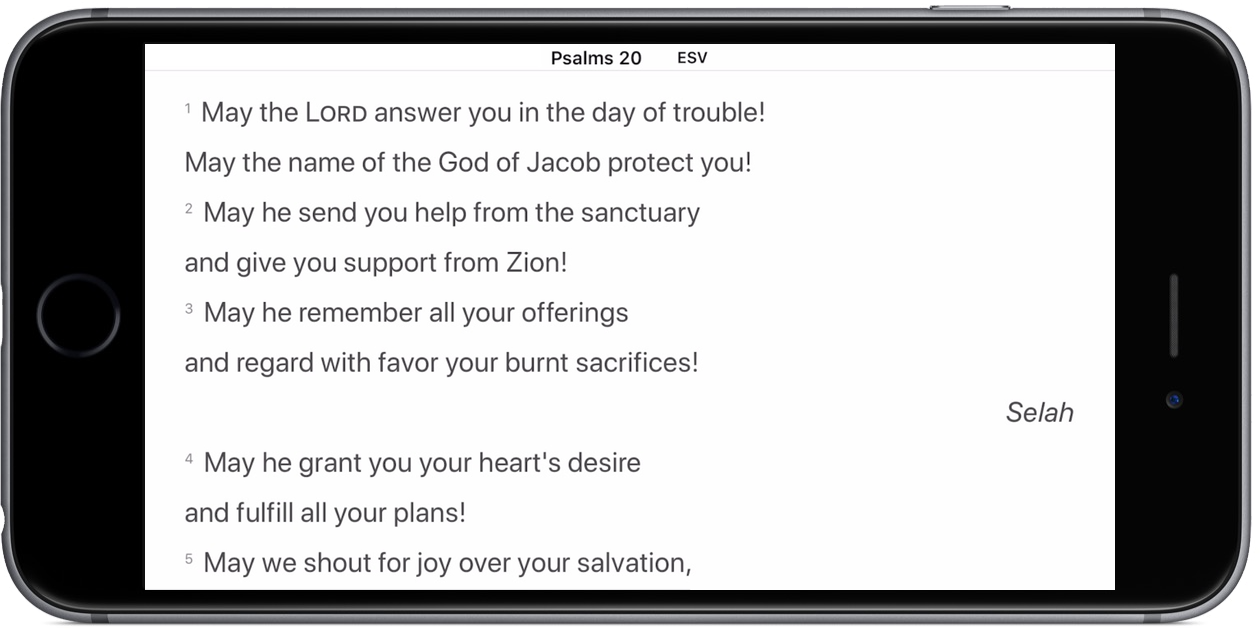

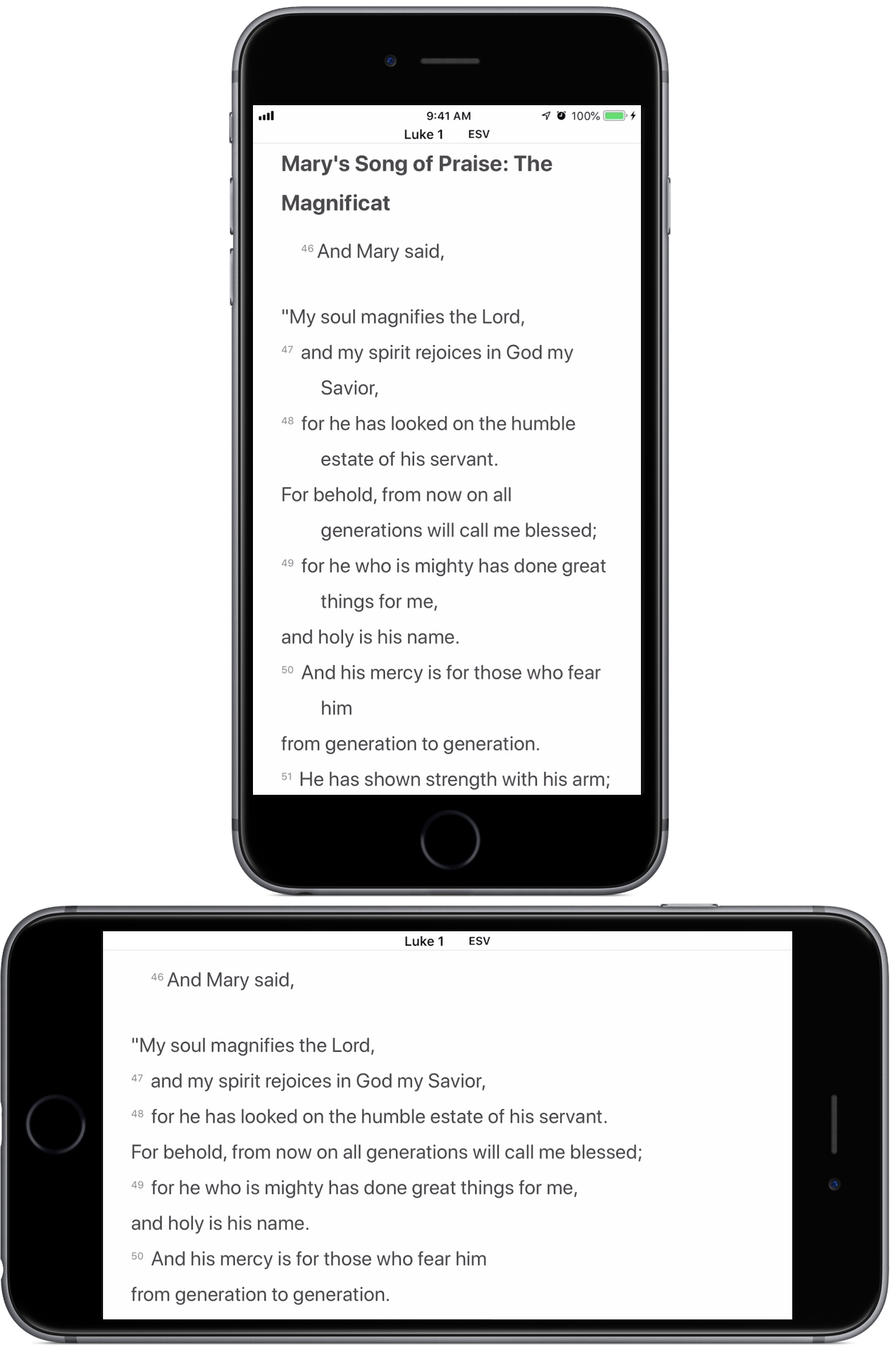

So with these barriers sitting in front of us, here’s the easiest thing to do to bring you a little closer to where you want to be today: turn your Bible sideways. Check it out:

Ta-da! Of those four barriers, one has disappeared with merely a change in perspective. Various other Bible apps, websites, and even physical Bibles can remove the other three for you, too.

A Few More Examples

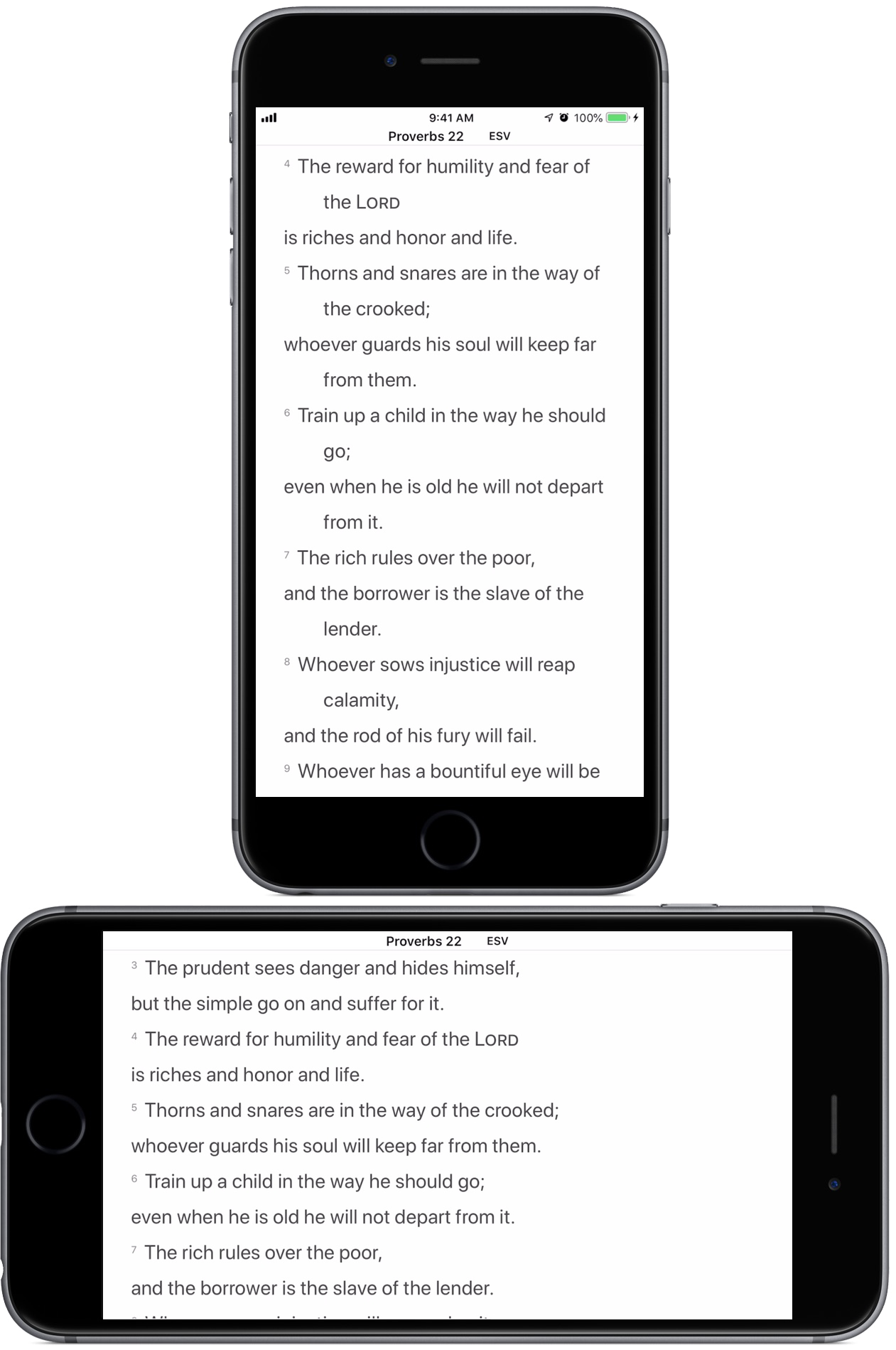

The psalms aren’t the only parts of Scripture where your phone might be misleading you. Here are three other types of passage where you should turn your Bible sideways.

We started with Psalms, so you might expect another candidate for sideways reading is Proverbs.

And you’d be right.

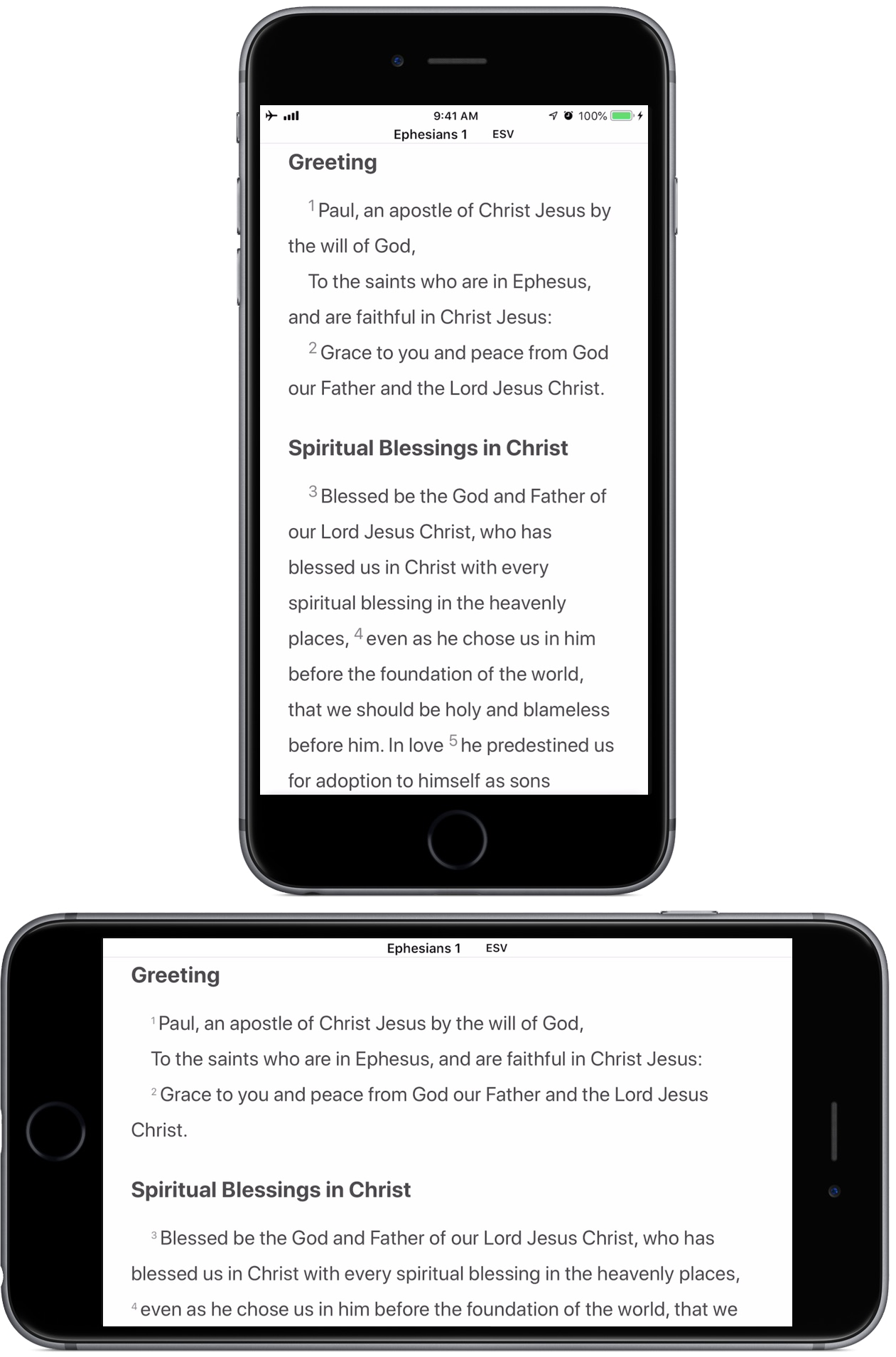

It’s not limited to poetry, though. Here’s Paul’s introduction to Ephesians, which, while not poetry, is quite structured.

Finally, here’s one last example. It’s a song, but from the New Testament. Mary’s Magnificat. Look closely: who would have guessed her pause before ‘from generation to generation’?

Scripture is twice-inspired. The Holy Spirit helped them write it and helps you read it. But you can help, too. Whenever you encounter something that doesn’t look quite right—turn your Bible sideways. It might just make things clearer than they used to be.

-

YouVersion, my favorite Bible app for devotionals. ↩